In 1996, Luzene Hill sat down in front of an easel and began sketching bones. Femurs, skulls, ribs — her mind was overwhelmed by the anatomy of death. She says she realized these skeletons were the remains of her Cherokee ancestors, and she titled the abstract series “In de Soto’s Path,” referring to the swath of disease and destruction the 16th-century Spanish conquistador and his men wrought on indigenous populations across the American Southeast.

The series became Hill’s first exhibit, debuting at the Santa Fe Indian Market in 1997. This milestone emerged three years after she was sexually assaulted at a park in Atlanta — the city where she was born and raised. “When that trauma happened … I knew I could either go through life wrapped in cotton wool — numb — or I could go through life feeling,” says Hill. She considers “In de Soto’s Path” a raw, personal investigation of her roots.

Though she spent summers visiting her paternal grandparents on the Qualla Boundary, where she now lives, Hill says her early sense of being Cherokee was more of an “intellectual exercise” than an emotional one.

“I have spent most of my life trying to find who I am,” Hill notes. Creative expression has been an integral part of her self-discovery.

In the ’80s, Hill began studying art as a student at Georgia State University. But when her grandparents and parents were faced with health issues, she put her studies aside to serve as a full-time caregiver.

“For 12 years, I traveled between Atlanta and Cherokee,” Hill remembers. With each move, she would box up her paints and brushes and canvases. “I was holding out hope,” she speculates. “That’s why I wouldn’t let them go.”

In 2007, Hill moved to Sylva to finish her BFA, and later her MFA, at Western Carolina University. Since then, she has used art as a medium for addressing issues of violence against women and indigenous cultures.

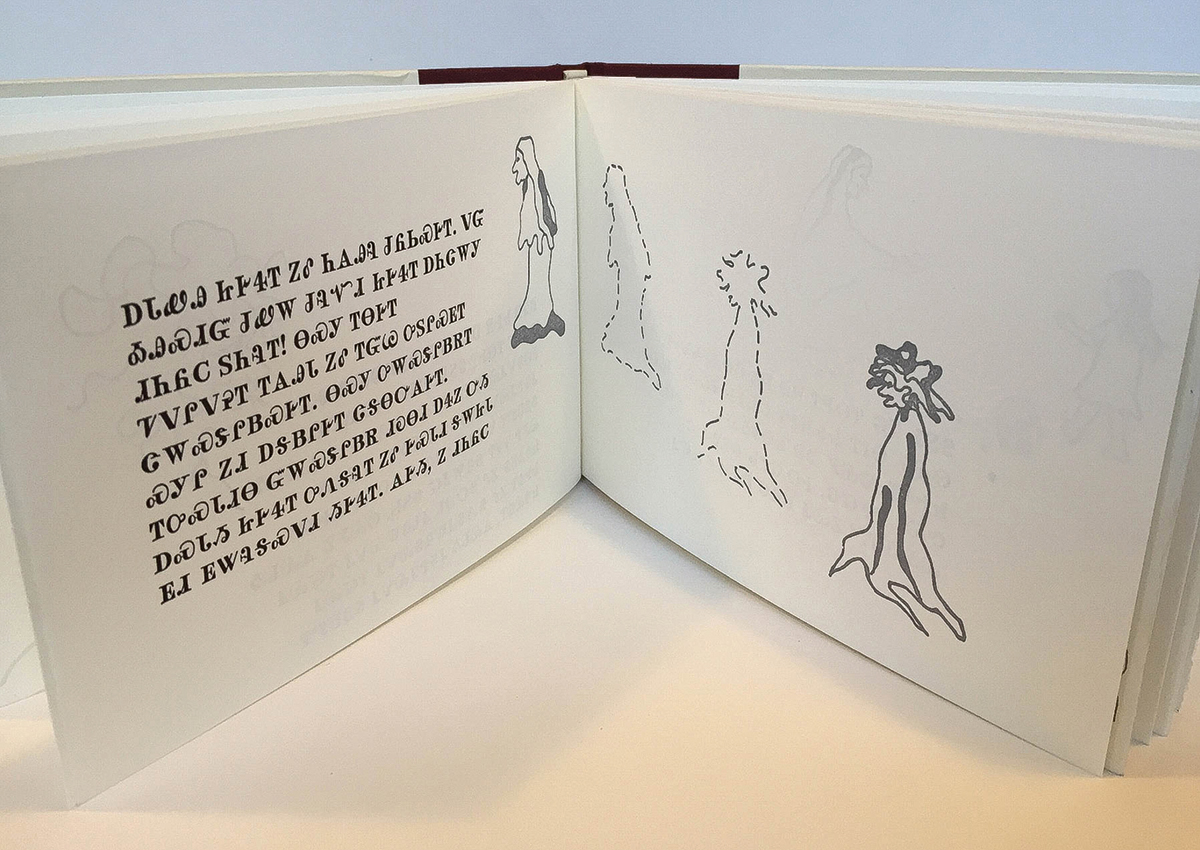

Though Hill still paints and draws, and has even partnered with WCU’s Cherokee Studies program to illustrate Cherokee syllabary books, the artist is best known for her highly conceptual performance installations. Retracing the Trace, for instance, centers around the creation of more than 3,000 khipu.

Traditionally, the Inca people fashioned khipu from strings and used them as recording devices — a means of collecting data, keeping census records, and so on. But in Hill’s installation, which debuted at the WCU Fine Art Museum in 2012, each khipu represented an unreported sexual assault in the United States.

Hill’s work has been shown across the country and around the world. One of her newest installations, created at deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum in New England last fall, is the activation/performance piece REVELATE. According to the artist, the work is about how females were once respected — nay, honored — in the pre-contact cultures of North America.

“Women were considered sacred because they were essential to the survival of the species,” says Hill. “In Cherokee society, women weren’t dominated. They weren’t treated like possessions. They weren’t assaulted.”

REVELATE, which Hill will recreate this winter at Asheville Art Museum, is a “counter-narrative to patriarchal colonialism,” she explains. “It’s an assertion of female power and sexuality.”

Luzene Hill, Cherokee, luzenehill.com. The artist’s local exhibits include participation in “Disruption,” a group show at the Museum of the Cherokee Indian, on display through next September (589 Tsali Blvd., Cherokee, mci.org); and “REVELATE,” opening at Asheville Art Museum (2 South Pack Square, Asheville) on Wednesday, Jan. 18, 2023, and running through May 15. (ashevilleart.org).