Chris Aluka Berry at home with Sasha in Madison County. For years, he has traversed northern Georgia, eastern Tennessee, and western North Carolina photographing the historic Black communities of Southern Appalachia.

Portrait by Lauren Rutten

Photographer Chris Aluka Berry recalls how he “used to go around with disposable cameras, all I could afford, taking photos of dirt roads and cotton fields. I’d ask photographers for advice, and eventually bought a camera and developed my style.”

When it came to human subjects, that style was “documentary with no posed portraits, just capturing the nuanced moments and subtle changes in body language.”

Mainly, he says, what he wanted to portray was “our shared humanity.”

In 2005, in his home state of South Carolina, he landed a job at the newspaper The State, where seasoned photographers mentored him. He entered the South Carolina News Photographers Association “Photographer of the Year” contest, winning top honors four times and coming in second four times.

In 2013, with the newspaper industry facing unprecedented challenges, he was laid off. But within a week, The New York Times published his photo of SC Gov. Mark Sanford (then campaigning for Congress) on its front page — “above the fold,” Berry notes.

He began to shoot for other major newspapers such as the Wall Street Journal and The Chicago Tribune — and became the go-to photographer for Reuters. Berry moved to Atlanta and found himself in big demand to cover special events. “I was photographing people like Tyler Perry, Will Smith, and Denzel Washington — while taking pictures of and talking with Jeff Bezos and his girlfriend.”

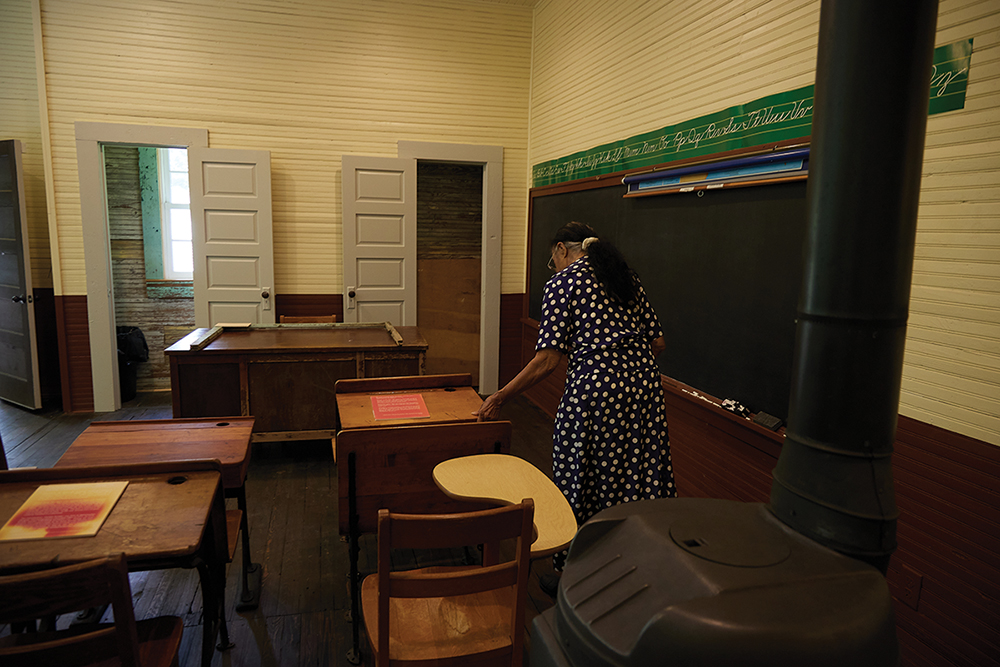

But he measured his success in much smaller moments, too. He recalls that in 2007, while documenting underfunded schools in South Carolina for The State, he photographed a middle-school student playing a tuba. A woman who saw it was shocked that the kids were playing such dinged-up instruments, so she arranged for a business to donate about 75 new instruments to the school, whose band started winning competitions. “That experience,” declares Berry, “opened my eyes to the power of documentary photography.”

In his online bio, Berry notes that “being raised in the South by a White mother and Black father, [I] traversed a complicated racial landscape.” He heard that there were historic Black communities in northern Georgia, western North Carolina, and eastern Tennessee whose members continue to “strongly identify with Appalachian culture.” Having always dreamed of living in the mountains, Berry began to investigate.

In 2015, he met Marie T. Cochran from Toccoa, Georgia, the founding curator of the Affrilachian Artist Project. In 2021, he met Marshall, North Carolina-based historian Maia A. Surdam, program director for the Partnership for Appalachian Girls’ Education. Surdam introduced him to people at the Smithsonian Institute — where a curator expressed interest in Berry’s photographs.

After much commuting, Berry finally relocated to Madison County last summer, and is set to release the first photography book particularly covering the African American communities of Southern Appalachia. Affrilachia: Testimonies, published by the University Press of Kentucky, reveals the vivid history and sustained presence of places such as Texana, a hamlet in the Great Smoky Mountains near Murphy, NC, founded by namesake matriarch Texana McClelland in the 1850s.

Berry contributed $16,000 so that the book would be elevated from a softcover release to an 11×11” hardback. He also hired Kelly Elaine Navies to write custom poetry for the book and Surdam to add context with historical essays.

“Raising that money was actually harder than doing the whole project,” Berry notes. “But it needed to be done. … Thirteen people I photographed for the book have already died since this project began.”

Chris Aluka Berry, Marshall, alukastories.com and on IG @alukastories.com. Berry will present a talk about Affrilachia: Testimonies with authors Kelly Elaine Navies and Maia Surdam at Weaverville Community Center (60 Lakeshore Drive) from 7-9pm on Friday, Oct. 11, and at Little Mount Zion Church (21 Hillside St., Weaverville) from 5-7pm on Saturday, Oct. 12. He’ll sign copies of his book at 6pm on Tuesday, Oct. 15 at Hub City Bookshop (186 West Main St., Spartanburg, SC, hubcity.org).

Having been a very close friend to Mr. Berry from the first instant photos all the way through the years, I remember sitting together in his study going through the projects and photos with him. As a first hand witness, I can say that his recognition is so very well deserved. He approached each and every single photo with a level of gravity and professionalism rarely seen. After decades of watching him grow in his passion of photography, I never once saw his dedication waver nor his demand (on himself) for excellence change.

Additionally, and equally impressive to me, in a dramatically changing field, he has managed to stay relevant and in demand throughout the years. Even laying his artistry in photography aside, his business sense in photography is outstanding in its own right.

BAM! That’s good work! BAM!

This is absolutely amazing!!! I always knew you’d do big things! This is HUGE!!! Job well done Chris!!