Photo by Clark Hodgin

Tyler Lavenburg is the head instructor at Weaverville’s Holistic Survival School. He uses his environment as material for his craftsmanship — hardcore homesteading skills including buckskin garment making, which he learned from local artisan Natalie Bogwalker. The school’s founder and director, Luke McLaughlin, notes that “the garments that Tyler makes are very symbolic [of] the whole rewilding movement. They are contradictory to all things that society deems important: they are extremely slow to make, physically and mentally challenging, custom made, connected to the local landscape, and deeply spiritual to the maker.”

Lavenburg leads Asheville Made through the laborious process.

Photo by Clark Hodgin

First, why go to so much effort?

I became fascinated by the transformation of a raw deer hide into the most incredibly soft and pliable material. After tanning a few hides, I found an old vest and cut it into a pattern, making it up as I went along. Even though it was absolutely imperfect when it was finished, I felt proud to have made something truly useful out of scratch.

Give an overview of the process …

Hide tanning is long and arduous. I procure most of my hides from wild-game processors that would have otherwise sent their hides to the landfill. They are fresh off the deer when I collect them. I then remove the rest of the flesh, the hair and the layer beneath that holds the hair in, which is called the grain layer. At this point only the dermis is left, which is the difference between buckskin [suede] and grain leather — what most boots, belts, and saddles are made out of. Once I scrape the hide down to the dermis, it’s ready to be immersed in the brine solution, which is the hide’s softening agent. It contains a fat known as lecithin, an essential ingredient in making the hide soft and pliable.

Once the hide has been saturated, it’s stretched until dry and then smoked over rotten [i.e., smokier] wood. The smoke seals the work I’ve just put into it so that it does not return to rawhide, which is very tough and not usable for garments.

How long does it take to finish?

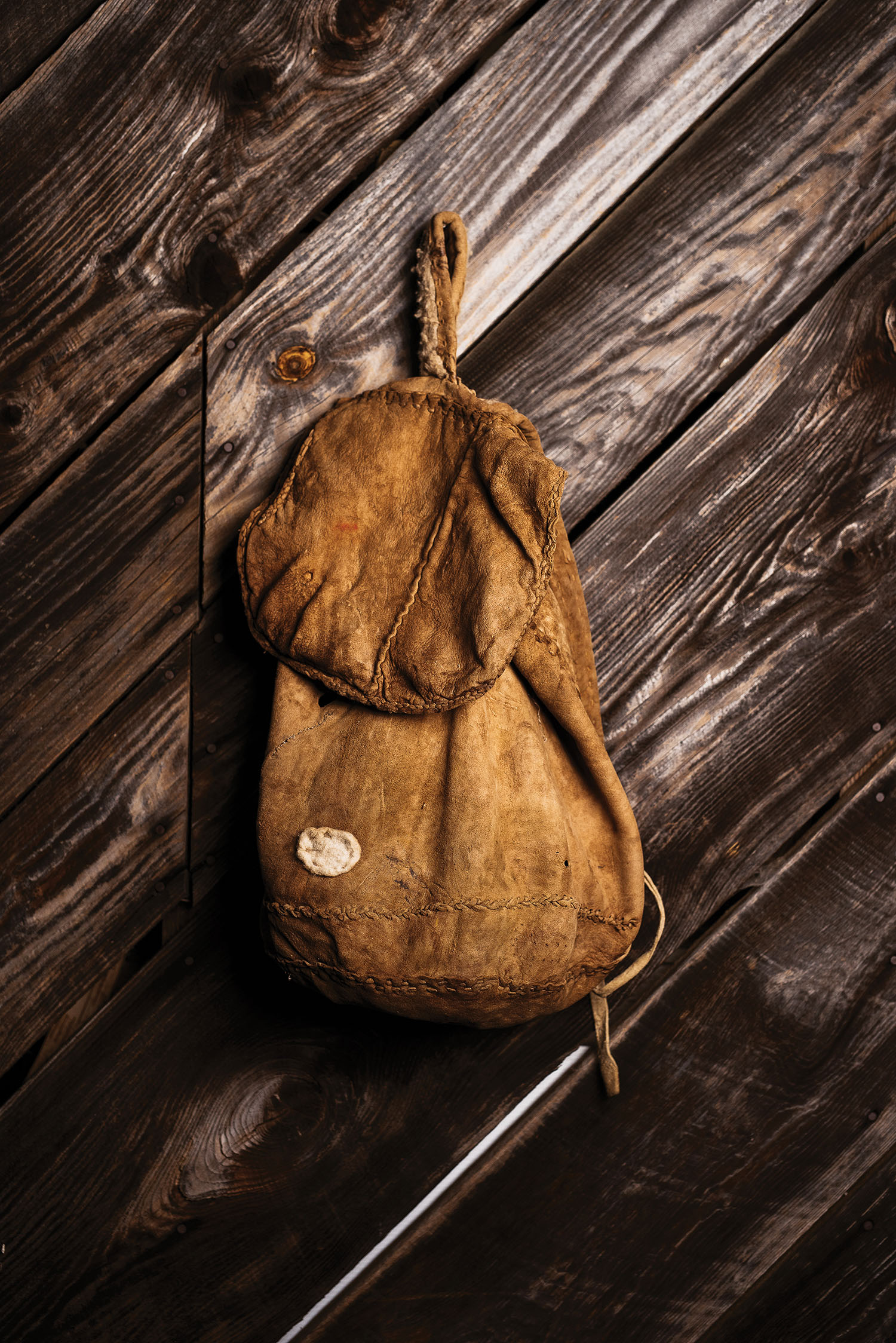

It takes a beginner about 24 hours per hide. Now, it only takes me about half that time. But most garments take multiple hides, so before sewing, say a jacket, there may already be 60 to 80 hours in the project. I sew all of my garments with leather lacing that I cut out of the buckskin, poke all the holes manually with an awl, and make the buttons from antlers, wood, seeds, nut shells, seashells, etc. It’s been really fun over the years to add things like fur trim and leaf appliqués, and to try out different stitches.

Do you make more than vests and jackets?

Since my first hides, I have made pants, shorts, multiple shirts, a coat, many bags, and even the clothes I got married in. [“When Tyler and Allie got married in their full buckskin attire, I thought, ‘What a loving and beautiful act of resistance,’” notes McLaughlin.]

Is it hard for the non-survivalist to find a good occasion to wear these garments?

A lot of people make their own clothing to replicate older fashion for re-enactments, but mine are everyday attire. They have real living energy — a powerful shift in how I feel in my body when I wear them. Buckskin is one of those magical transformations in the natural world that is a true gift from the animals. In utilizing this resource that would have otherwise gone to the trash, I am able to give the material new life and reclaim an art form that was once practiced by nearly every traditional culture in the world.

Photos by Clark Hodgin

Tyler Lavenburg, Holistic Survival School, Weaverville. For information about the school’s wide variety of traditional-skills workshops, see holisticsurvivalschool.com.