scouting weaving patterns.

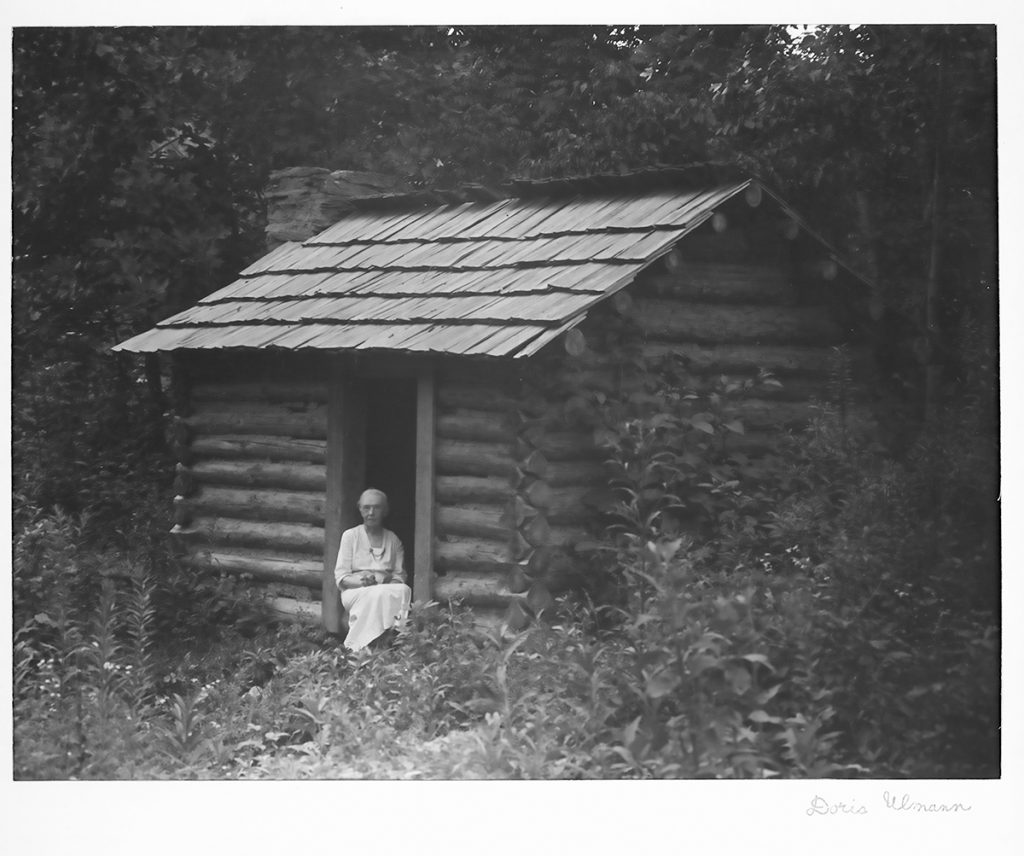

(Period photos courtesy of the Southern Highland Craft Guild.)

Frances Louisa Goodrich (1856-1944) was a Presbyterian missionary from Binghamton, New York, who came to Buncombe County — living in East Asheville’s Riceville community and Brittain Cove, near Weaverville — and then moved northwest into Madison County. A Yale-educated painter and the great granddaughter of Noah Webster, author of the first dictionary, she ended up playing a vital role in preserving handcrafted textiles in Western North Carolina, especially weaving. Goodrich founded Allanstand Cottage Industries in 1897 (later the Allanstand Craft Shop); she gifted the assets of Allanstand to the nascent Southern Highland Craft Guild, which helped the young organization financially support itself by having an established market.

Weaver and historian Danielle Burke, program coordinator for the Masters of Art in Critical Craft Studies program at Warren Wilson College, has extensively researched Goodrich’s life and work. Burke’s own current work focuses on vernacular historical weaving patterns and can be found in venues including the Asheville Art Museum’s re-opening exhibit Appalachia Now!, slated for fall, and in “Coined in the South,” a juried show at the Mint Museum in Charlotte.

What do you regard as Frances Goodrich’s most valuable

contribution?

She was an archivist who had a fascination with weaving and documenting the patterns for weavings. That’s really important, because now we have this material to work with 100 years later. She probably collected hundreds of patterns by going around all alone on horseback through the mountains. I can’t imagine what that was like. She also gave encouragement to women to start weaving again, by facilitating some forgotten pride. Sometimes it takes someone who is not from a community to say, “This is really a great thing you guys are doing,” and inspire them.

How were those weaving patterns recorded?

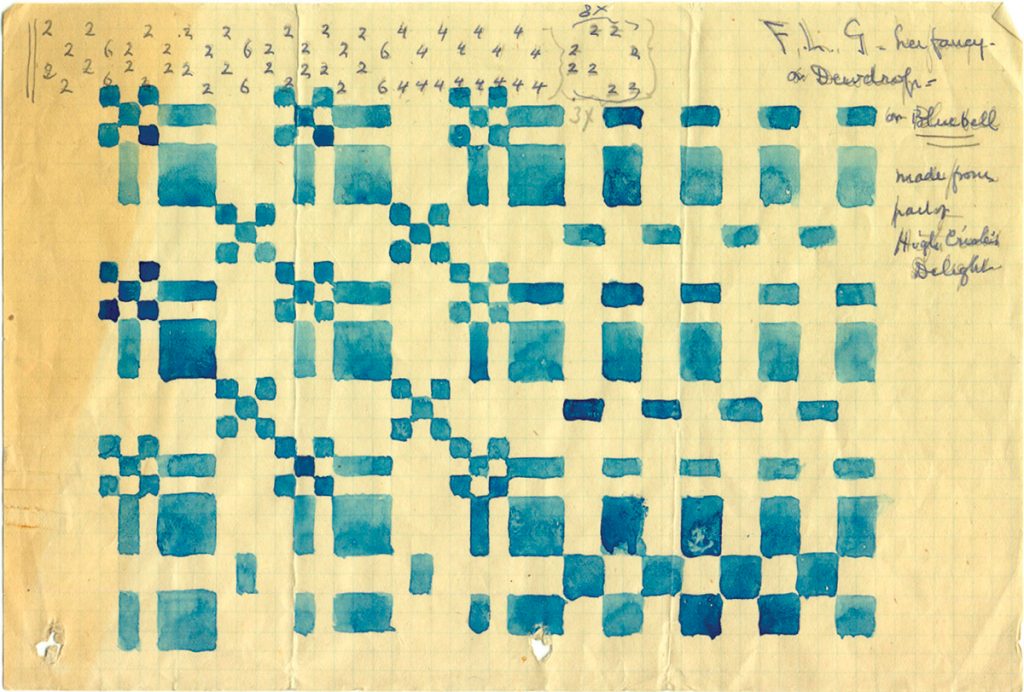

The pattern would have been written on a long strip of paper; [it would] look like a string of lines or numbers, like a long math problem. From looking at that, the weaver knew how to set up their loom. But only after weaving it would they actually get to see what the pattern looked like.

They did all that work, with no idea what the finished product would look like?

Yeah, it’s kind of a risk, although they may have known if they had coverlets or other weavings in the family made from the same draft. But Frances collected the drafts and then did watercolors of the patterns to go with them.

So you’d have a visual rendering to preview the pattern?

Yes, and she did a good job of recording colloquial names of drafts. [It’s] the only way we have of hearing the voices of the weavers and their stories.

An oral history communicated by giving a pattern a name?

Yes, and that was important for a region where literacy was low and paper was scarce.

Can you give an example of how that works?

The name of one pattern Goodrich archived was originally recorded as “Pokendalis.” That’s a phonetic spelling of Polk and Dallas. President of the United States Polk, and Vice President Dallas.

So that could date the pattern and give it context, not with any visual clues, but just through the title?

Yes. Another pattern is called “Swepson and Littlefield.” They were two guys who stole money meant to fund a railroad project that was about to connect a remote mountain community to the rest of the world.

Who would have thought that a blanket is there to keep you warm, but [can] also tell a story about a robbery?

It gives new meaning to the syllable “text” in textiles.

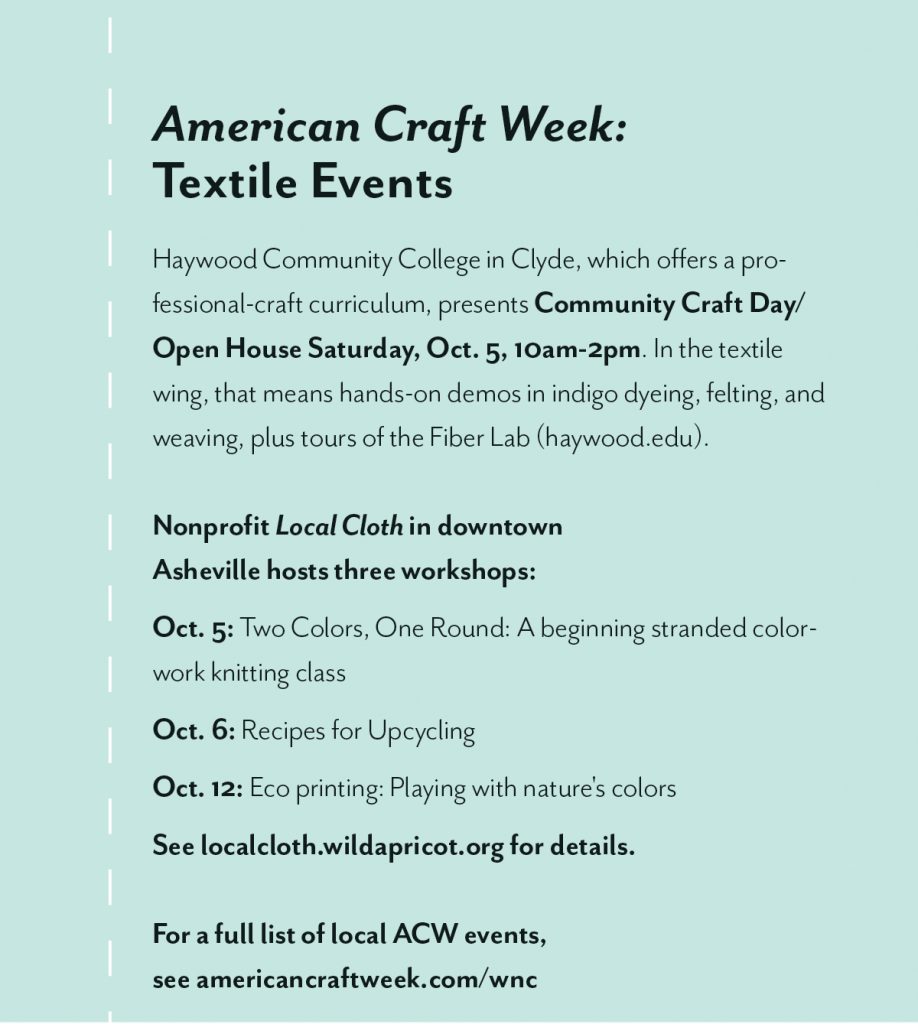

Frances Louisa Goodrich’s textile collection and watercolor depictions of weave drafts are on display in the permanent collection of the Southern Highland Craft Guild at the Folk Art Center (382 Blue Ridge Pkwy., Asheville). For more information on Danielle Burke, see daniellelouiseburke.com and on Instagram: @dani.burke.

Thank you for bringing attention to Frances Goodrich. She, along with other strong women, blazed a trail of crafts through this region.