Sculptor Thomas Schram channels nature’s resilience.

Photo by Clay Nations Photography

Pine trees have their limits. Asheville sculptor and art educator Thomas Schram learned this as a young boy growing up in North Carolina’s Piedmont region, where he spent countless hours playing among the pines.

According to Schram, the trees were nearly impossible to climb because of their fragile branches. They would also leave his clothes sticky with sap. “… But still, those spaces represented a welcoming and peaceful place to play and explore,” he remembers.

Later, when Schram was working at the Lamar Dodd School of Art at the University of Georgia, he thought a lot about those conifers — specifically, their demise, in order to meet the wide demand for corrugated cardboard.

“… I would routinely amass piles of cardboard boxes in unpacking materials ordered for sculpture studio classes,” he explains. “While cardboard is one of the most recyclable materials, there is still a societal disregard for where this material comes from, as is true of many contemporary materials.”

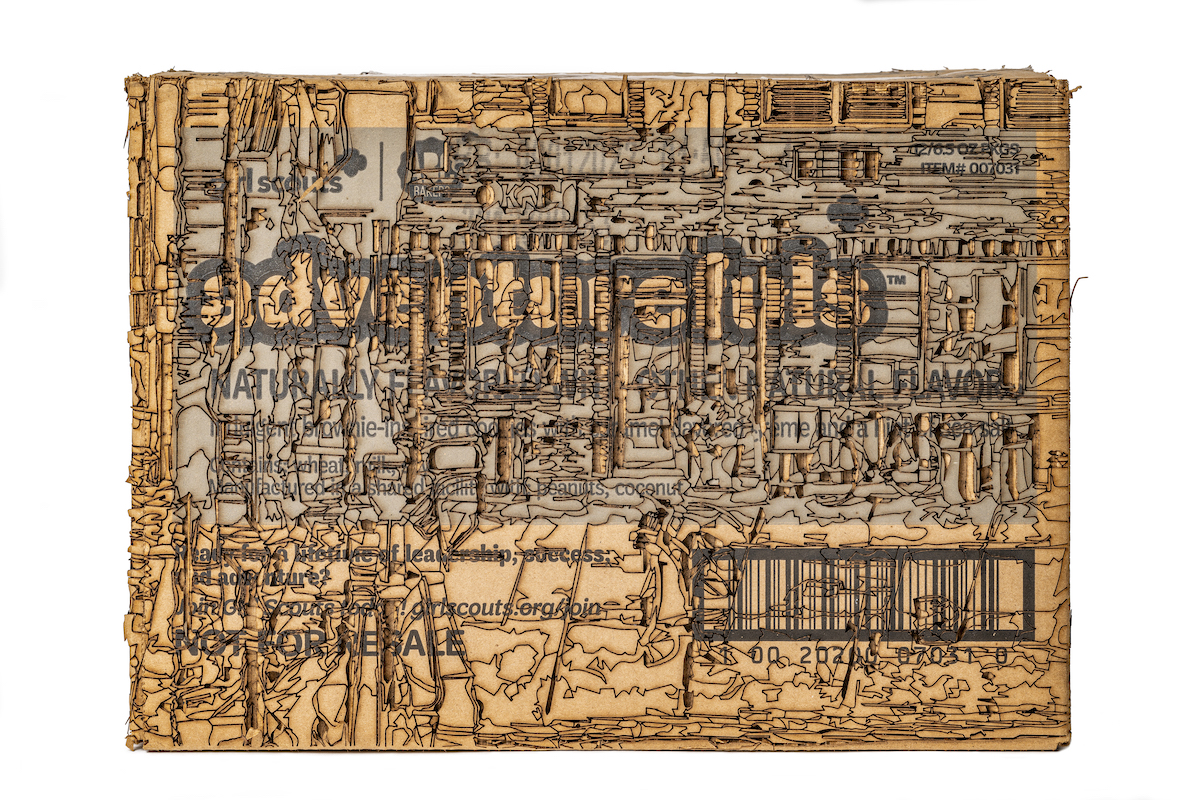

Meditating on this dynamic, Schram began using a digital laser cutter to incise jettisoned cardboard boxes with a densely choreographed orchestration of marks, including textures suggestive of pine needles and bark. The resulting sculptures, some taking 25 hours to complete, highlight “the transition of this material from tree to crop to commodity to anonymous logistics aid.”

This series also inspired Schram to adopt an all-new approach to sourcing materials. He calls it “Post Consumer Makers.”

In this process, “materials aren’t searched for and found — as is true with many found-object sculptures — but are saved in a moment when they would otherwise be discarded,” says Schram. “These materials are then used to create the work. This methodology is now my primary way of sourcing all materials I use.”

For his latest project, the artist salvaged detritus from the wreckage of Hurricane Helene, including scrap from a metal shed crushed by two pines, branches from said pines, shredded fiber-optic cables, a waterlogged dresser, and potable-water boxes. He used these bits to sculpt a flume (a type of trough used by loggers to move timber) in the shape of the French Broad River, onto which a video of moving water has been projected.

The piece is currently on display as part of Holding Water, a solo exhibition at The Bascom in Highlands, where Schram served as the 2024 to 2025 Winter Resident Artist. (He is also Visiting Assistant Professor of Sculpture at Western Carolina University in Cullowhee.)

“I saw this project as an opportunity to reflect on the events of last fall and my experiences of them, but to also see the storm as a link in a chain,” says Schram. “This region has a long relationship with the land, its waterways, and its trees. Through logging and the birth of forestry, past floods, and past storms, we have had a powerful and dynamic relationship with the land and its resources.

“There is toughness and resilience on all sides. I hope the exhibition feels somber and quiet, bringing some space for reflection on our history and present.”

Thomas Schram, Asheville, tomschram.net. Holding Water runs at The Bascom: Center for the Visual Arts (323 Franklin Road, Highlands, thebascom.org) through Saturday, May 10. Schram’s work is also on display at the Bardo Arts Center at Western Carolina University’s Fine Arts Museum (199 Centennial Drive) as part of the Biennial Faculty Exhibition, wcu.edu/bardo-arts-center, through Friday, May 2.