For the most part, the fabric of Asheville’s arts scene is tight-knit. Creatives find camaraderie in reimagined industrial areas like the River Arts District and along charming routes such as Beaverdam Valley and the Weaverville surround, which both hold annual studio tours.

But there’s one place where the tapestry unravels.

“It’s a wasteland,” says mixed-media artist and Biltmore Lake resident Louise Glickman, referring not to a lack of individual talent but to the absence of a unifying cultural presence in her neighborhood and others running along the Smoky Park Highway corridor.

A semi-rural locale traditionally punctuated by industry, the Enka-Candler area turns up little in the way of galleries, studio tours, and other concerted efforts to showcase the arts. Again, the problem isn’t that few creative-minded people dare to live west of Haywood Road. (In fact, many artists are fleeing Asheville’s more urban districts for cheaper real estate.) Rather, the challenge lies in rallying dozens of micro-neighborhoods whose residents vary greatly in demographics.

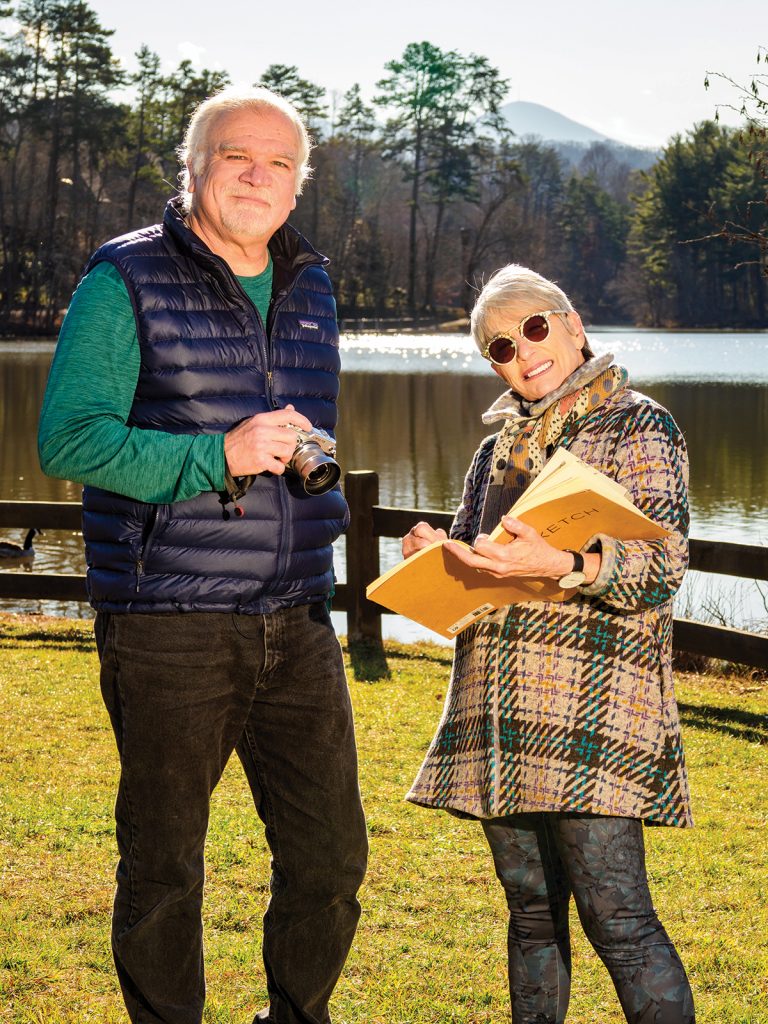

But if anyone could unite a markedly disjointed community, it would be Glickman. A former New Orleans resident with decades of marketing experience, Glickman founded a small, hyperlocal artists collective called Biltmore Lake Artists in 2019, after a visual impairment left her unable to drive to downtown galleries. In May 2020, in hopes of expanding the group’s reach and remedying pandemic loneliness, Biltmore Lake Artists officially evolved into the Sand Hill Artists Collective, an organization that celebrates crafters and artists living around Sand Hill Road. The road winds from the heart of the West Asheville business corridor past Vance Elementary School and the terminus of Hominy Creek Greenway; through Enka Village, a former textile hub where the American Enka Company was once the largest national producer of rayon, and where the eco-friendly fabric Lyocell (aka Tencel) was born; to Biltmore Lake, an upscale planned community. (The lake, created 100 years ago for factory employees, is now private.)

Like most aspects of pandemic life, the collective is an exclusively virtual endeavor for now. Fellow Biltmore Lake resident Bob Ware maintains a blog that, in addition to being a platform for art news and commentary, features three artists each month. “He’s been with me since the beginning [of the project],” notes Glickman. “I owe him everything.”

To be eligible for the collective, the artist must live or work in one of five Buncombe County zip codes: 28715, 28728, 28704, 28806, or 28810. The artist’s work must also be screened by a five-member jury of local makers and gallery professionals.

“We want to represent a variety of mediums and talent levels,” says Glickman. “One of our goals is to provide exposure to emerging artists.”

Case in point: painter Gail Sauter. Though Sauter is well known in the creative communities spidering out from Portland, Maine — she served as Acadia National Park’s artist-in-residence in 2010 — she is new to North Carolina. Two winters ago, she went knocking around in a travel trailer, looking for a warmer place to hang her hat. When she rolled into Asheville, she fell in love with a city whose artists are front and center. “It’s a place where the public can actually see the makers,” says Sauter.

In March, amid Governor Cooper’s first round of stay-at-home orders, she put down roots in the western reaches of Buncombe County. Her style — one that is clearly influenced by 19th-century Impressionism — brings a new flavor to the local arts scene. Much like American painter Mary Cassatt, Sauter’s works are atmospheric. They capture the body language of women walking in crowded streets and children swimming in indigo water.

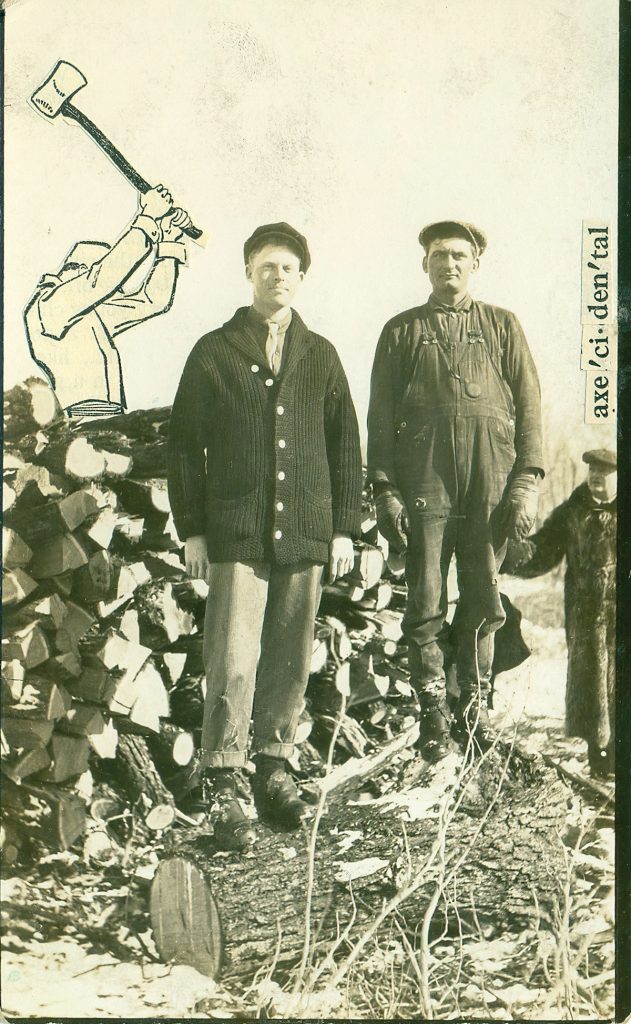

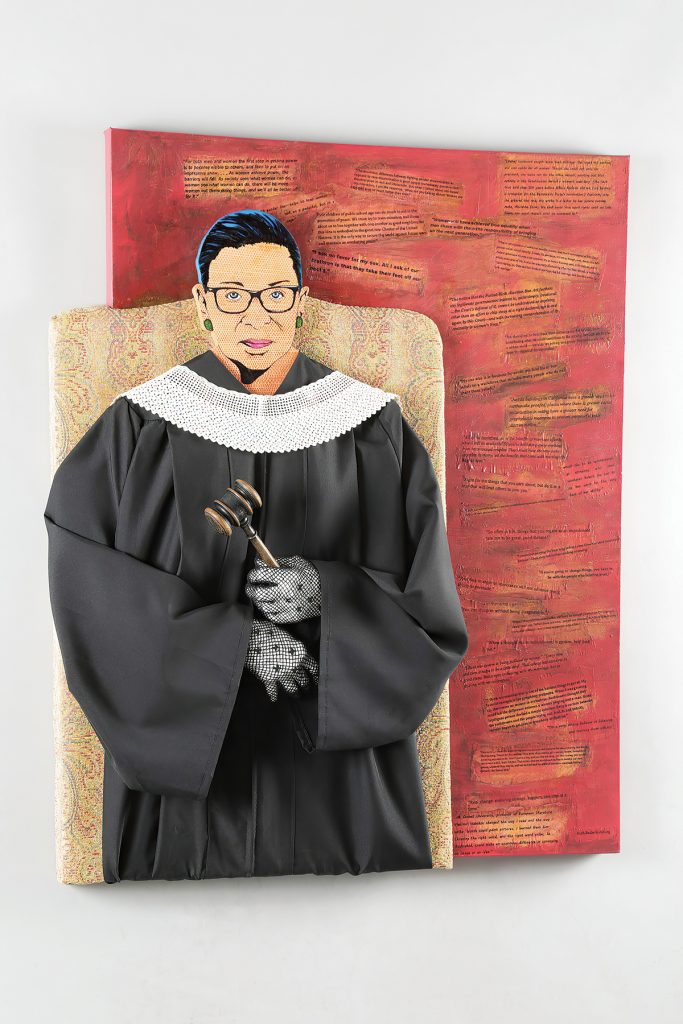

Sauter was featured on the blog late last year, joining other area painters such as Joseph Pearson, whose figurative work includes sociopolitical narratives centered on the Black community and emotionally resonant portraiture, and self-proclaimed “poly-crafter” Terry Taylor. An Enka native — his mother was born in the agrarian community of Big Sandy Mush, north of Leicester, and his father in Candler’s Billy Cove — Taylor is deeply rooted in these mountains. Even his current work focuses on transforming vintage postcards from Western North Carolina.

Taylor admits that the region is a cultural dustbowl. “Enka and Candler aren’t exactly artistic hotbeds,” Taylor says. “Few galleries? How about no galleries?”

Needless to say, the Sand Hill Artists Collective meets a need. That much is evident in blog traffic. In less than nine months, the website has garnered more than 500 subscribers, 40 percent of whom are from out of town. Glickman attributes the organization’s success to old-school, word-of-mouth marketing. “That’s what I do,” she laughs.

Major Asheville galleries such as Blue Spiral 1, whose director Michael Manes lives in Enka Village and serves as an advisor to the collective, also helped by networking with artists. In December, gallery professionals banded together with the Sand Hill Artists Collective to produce a Virtual Holiday Gallery Tour, an online series featuring original programming from ten of the Asheville area’s top galleries. The money raised will fund a part-time social-media-marketing position in 2021.

“The collective has grown organically,” says Glickman. “We had zero money, just a goal of connecting communities and providing artists with support, and we did it.”

To learn more about the Sand Hill Artists Collective, visit sandhillartists.com. For more information, e-mail Louise Glickman at lsglickman@gmail.com.