Photo by Morgan Ford

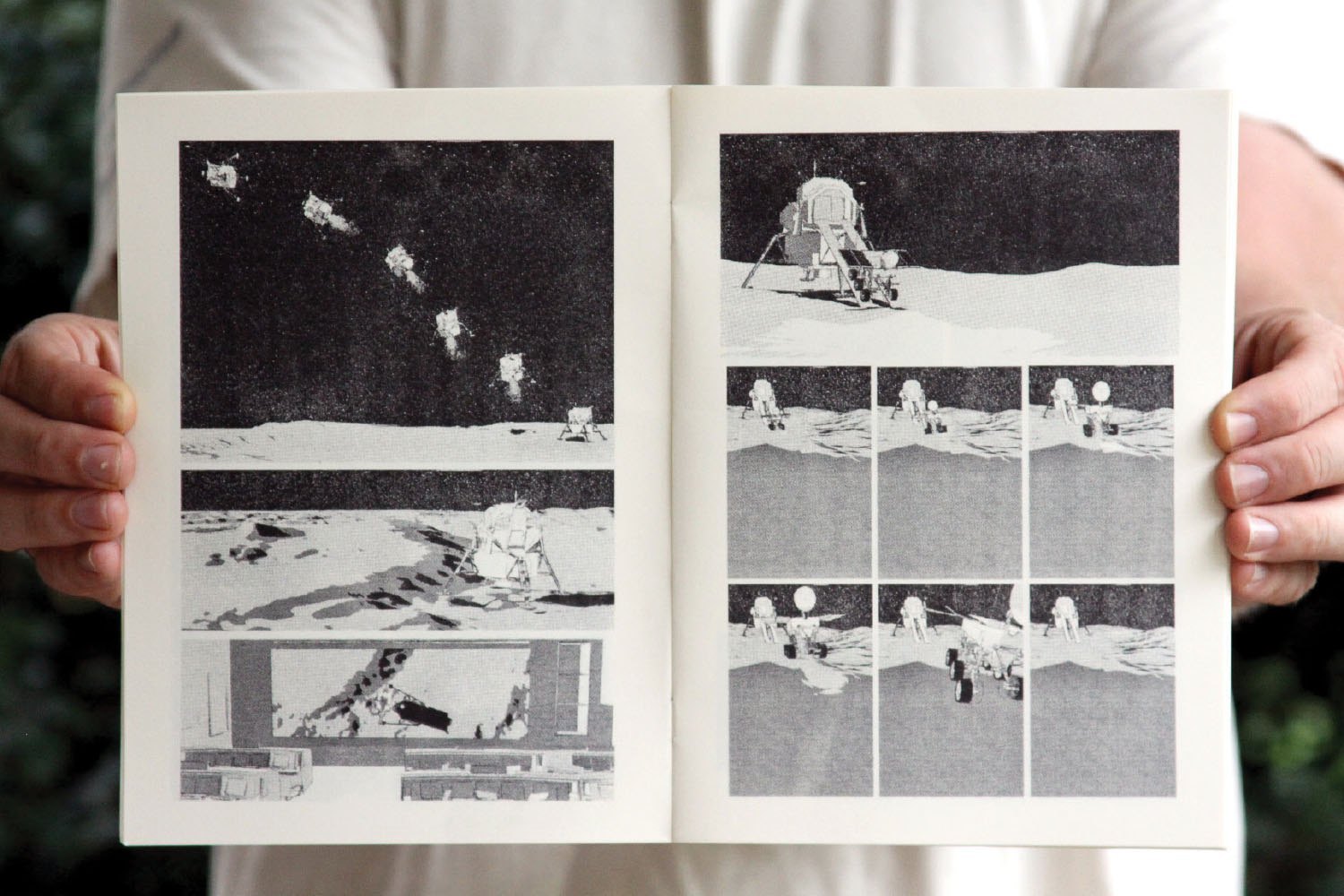

Mica Mead and Colin Sutherland launched Woolly Press in 2013, after discovering the unique aesthetic potential of a circa-1986 printer called the Risograph. The obscure, virtually obsolete Japanese-made machine is computerized and digital. But ink is applied in layers with drum rollers, through a perforated master stencil. That provides a rich visual texture and organic quality comparable to silkscreen printing.

What distinguishes Risograph printing?

Colin: Each layer of color is loaded on top of the previous one, which lends itself to a hand-printed aesthetic. That really appeals to people wanting to do things like posters, books, and comics.

Mica: Nothing else compares. All the time I see things people printed and think, “They should have used a Riso.” It’s also cheaper and faster.

Colin: And there’s no toxic toner; it’s liquid soy ink.

So it’s gluten-free?

Colin (laughter): Yeah, and everything we print is on recycled paper.

Do many print shops offer Risograph services?

Colin: There are currently only 198 in North America. When we started, I’d guess there were about a dozen.

How’d you get into this?

Mica: This was all Colin’s idea. You have to understand, Colin has lots of hobbies. The next thing I know, a Riso shows up at our house.

Why?

Colin: I’ve always done drawing and illustration, and I do children’s books and comics. When I saw printing done with a Riso, I loved it and wanted to understand more. So I got a used one and four color drums on eBay.

Mica: With four colors we can theoretically mix any color in the rainbow.

Can you still get parts?

Colin: You can’t get new parts. We downloaded tech manuals from a sketchy Russian website and do all of our own repairs.

Isn’t that a headache?

Colin: They’re finicky and labor intensive. A retired teacher told me she used a Riso every day in her career and hated printing on it.

Mica: But it’s a perfect machine for us, because you gets lots of artifacts from the printing process that we and other artists value and embrace.

What do you mean by artifacts?

Colin: Track marks from what you printed before, or if the master gets a wrinkle, you get an interesting footprint that you may want to keep. We still have control over the printing process. But we also have a bit of poetic license.

How did your Riso curiosity evolve into a business?

Colin: Sort of unintentionally. We were printing for friends and family and outgrew our kitchen. So we had to get a bigger space and ended up with a business license and a shop.

Mica: I studied art, but never saw myself becoming a printmaker. I was mainly drawn in because my brother is a cartoonist, my father is a poet, and Colin’s an illustrator. I had this lovely instrument for taking their projects and putting them out there. I’m glad I landed here. It’s really satisfying.

Does a Riso look cool?

Mica: It’s pretty anticlimactic looking. People come to the shop thinking they’re going to see a beautiful letterpress machine or something, and they’re kind of disappointed.

Colin: We make enamel pins that have a little Riso on them. When I wear mine, people always say, “Why do you have a washing machine pin on your lapel?”

Mica: But they sell like hotcakes.

Really? Who buys Riso lapel pins?

Colin: There’s been a Riso revival, so there’s a worldwide Risograph subculture in the artistic community.

How does the manufacturer feel about that?

Colin: They could make money off of it, but they almost refuse to acknowledge it.

Is that because artists like you highlight and celebrate the machine’s technical flaws?

Colin: I never thought about it that way, but I guess that’s right.

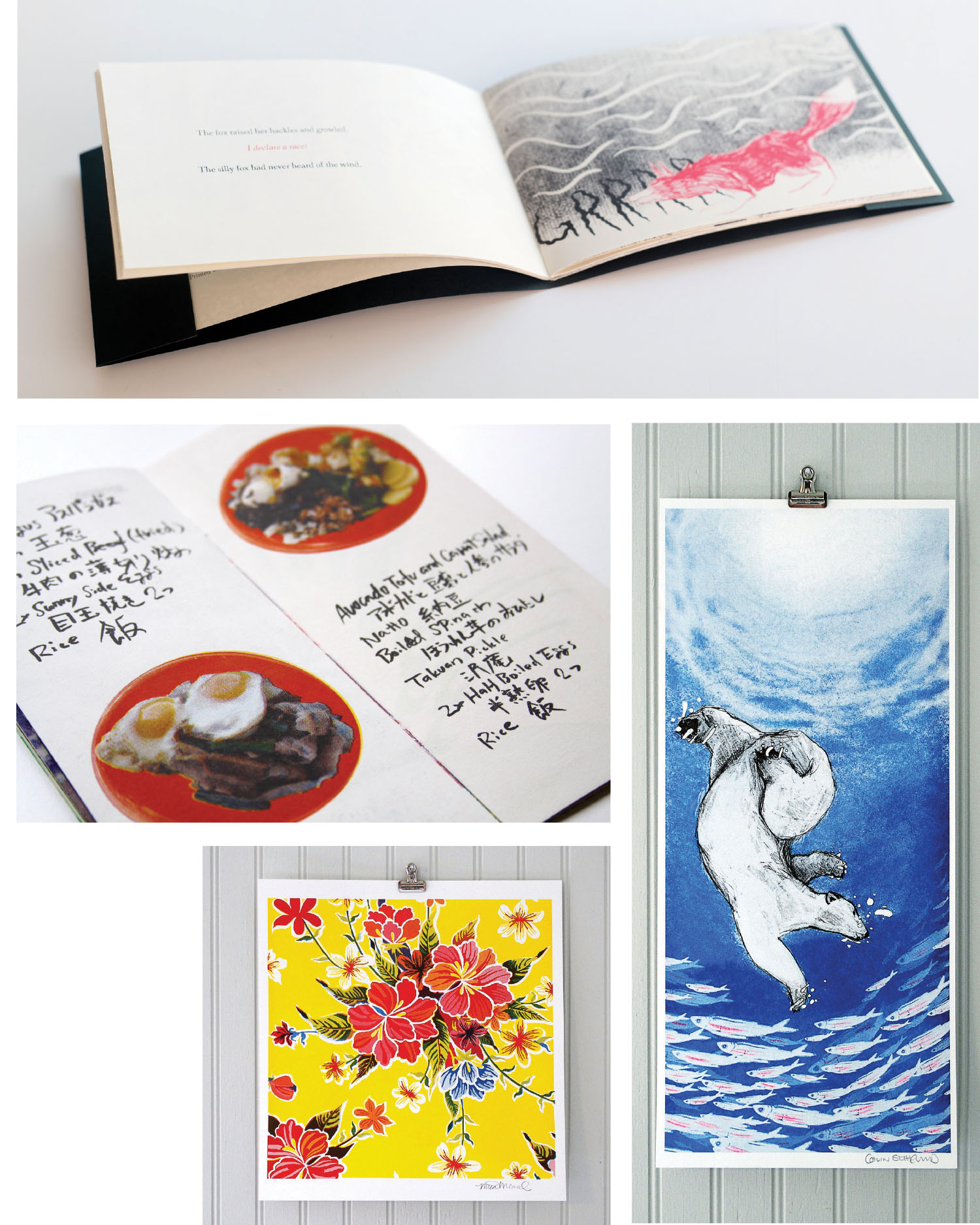

RIGHT: Oilcloth

by Mica Mead

FAR RIGHT: Fishing,

by Colin Sutherland

Mica Mead and Colin Sutherland, Woolly Press (178-B Westwood Place, West Asheville). See woollypress.com for more information. They are also on Facebook and Instagram (@woollypress). To schedule a shop visit, e-mail info@woollypress.com.