Portrait by Clark Hodgin

Across America, a culture war is raging, says painter John Mac Kah. But he’s not referencing current social movements or political turmoil. “There’s a war on realism in the art world,” he insists. “Most universities and art schools disdain realism these days.” In academia, he says, “it’s all about emotion and abstraction.”

But realist painters like Mac Kah, who sees himself as part of the American tradition of landscape painters and portrait artists, have been pushing back. “What’s happening is that places devoted to realism painting are cropping up all over the country, as a counterbalance. It’s been building for the past 20 years. They develop real portrait painters and landscape artists who are working from life in the classical tradition.”

Mac Kah cites the Florence Academy of Art in Italy as a primary source of momentum in the realism renaissance. “A lot from that classical school has been transferred to America,” he says. The painter has been offering the same kind of instruction for decades, in his studio and at regional institutions including Penland School of Craft, the John C. Campbell Folk School, and Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts. (He’s also co-founder of The Saints of Paint, a group of artists who raise money for local causes.)

In his classes, Mac Kah teaches an intensive understanding of fundamentals. Students learn about pigments and how to make oil mediums to produce the kind of light refraction found in the Old Masters paintings. There aren’t any shortcuts: The students make their own gesso and their own panels, over which they stretch linen. “You are much more respectful to the materials,” explains Mac Kah, “if you make them yourself. That investment, even before you start a painting, translates, I believe, to the viewer. I really believe there’s an energy you instill in the piece. Color theory and the rest comes after you get the foundation. You first have to understand how the paint works. We want to keep these methods alive in a sea of untrained work.”

These centuries-old techniques were used by Rembrandt, and they enable Mac Kah to achieve the ethereal effects in his own landscapes. Empowered with classical skills and insights, Mac Kah says, artists can execute their vision more successfully, even if they’re painting abstracts.

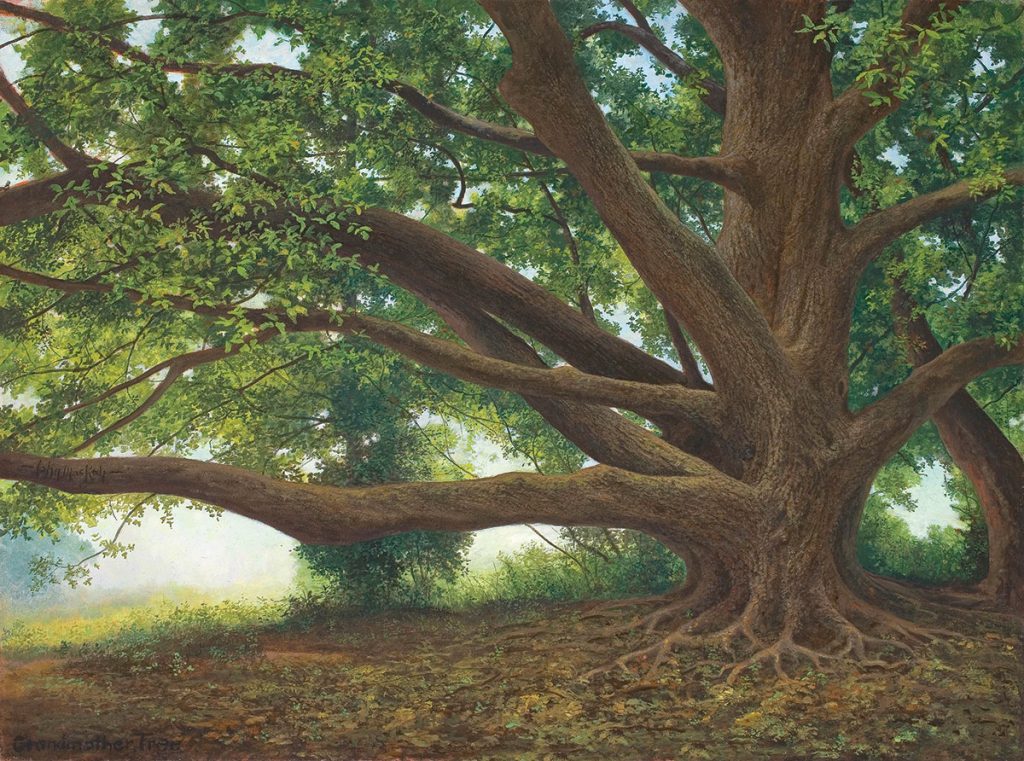

Old Masters aside, Mac Kah’s deepest muse is alive and well. “I’m on my knees to nature all the time,” says the painter. I don’t get my jollies from making stuff up in the studio. You’ll be outside and see the scene, and in that instant you know it’s a painting and a winner. The problem is keeping that synapse alive all through the painting process.”

He may go back to same spot eight or nine times to become more intimate with the subject and pinpoint the best lighting to capture. “Realism is the search for the true line, the true form, the true light. Part of the love is the challenge of getting the painting to have a presence and a spirit. That’s where we want to go, where the magic happens.”

John Mac Kah, Asheville. The painter’s work is represented by Grand Bohemian Gallery of the Kessler Collection, 11 Boston Way, in Biltmore Village (www.kesslercollection.com/gallery) and by Martin House Gallery in Blowing Rock (martinhousegallery.com). Mac Kah will host a workshop, “The Painter’s Craft: Renaissance Materials and Methods,” in his JMK Studio236 (at Riverview Station, 191 Lyman St. in the River Arts District) Friday, Dec. 4 and Saturday, Dec. 5, 10am-3pm, following COVID-19 protocols for social distancing. For more information, see johnmackah.com. Also on Instagram: @jmkah236.