Legacy Crafters Series | Part 2

Ten years in, Murrial Martin took over the woodworking program.

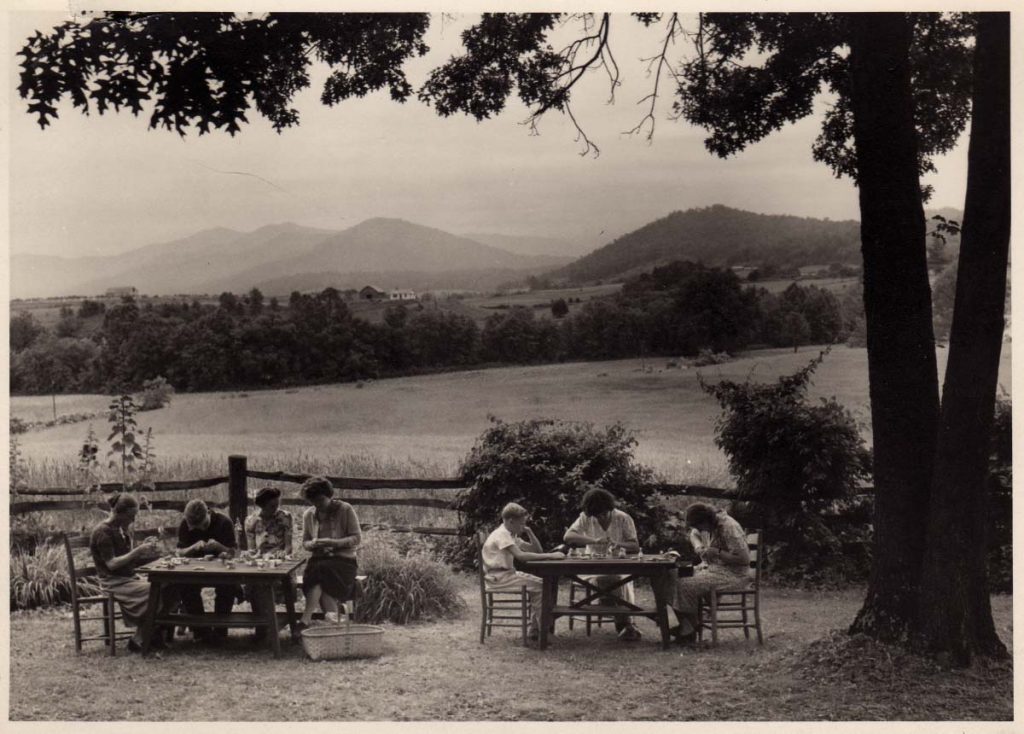

Photo used courtesy John C. Campbell Folk School

Murrial “Murray” Martin (1903-2005) supervised the John C. Campbell Folk School woodcarving program from 1935 to 1973. Her students, at first mostly men and later mostly women, ranged in age from early teens to early seventies. They were known as the Brasstown Carvers, and many struggled with conditions of abject poverty. But Martin’s program was able to transform some of the artisans’ lives — economically, socially, educationally, and culturally. Mary Doornbos, manager and buyer for the John C Campbell Folk School Craft Shop, knew Martin as a friend and mentor.

Photo used courtesy John C. Campbell Folk School

What inspired the carving program?

Olive Campbell [wife of John Campbell and co-founder of the folk school] saw men sitting on a bench in Brasstown whittling to see who could make the longest wood shaving. Olive thought it was idle competition, and if they could do that, they could carve.

To earn a better living?

She wasn’t so much thinking of the money they could earn as the pleasure of creating and how that would expand their lives. Olive’s favorite quote, which is the reason I came here, was “Awaken, enliven, enlighten.”

So she hired Murray Martin to awaken the carving program?

Yes. Murray was teaching rehabilitation crafts to World War I vets at Walter Reed Hospital. Her last name before she got married was Decker. She was part of the family that started the Black + Decker tool company.

Photos used courtesy John C. Campbell Folk School

Crafting was in her DNA, then. How’d you befriend Murray?

My husband and daughter and I moved here in 1997, and Murray lived on campus until her death when she was almost 102. When Olive hired her, Murrial didn’t think she was going to be here for more than six months; she’d just ditty-bop down here and go back. But it became her life’s work, and she was extraordinarily happy to do it and make a difference.

What kind of difference?

Carving enabled people to let their kids stay in school longer or build an indoor bathroom. Women during WWII would buy war bonds with carving money. Women were augmenting their income and expanding their lives. My friend Hope Brown, one of Murray’s students, told me, “My daughter became a lawyer because of carving.” That’s the kind of influence Murray and the Folk School had.

Carving meant access to a completely different world?

A woman whose husband was a carver said the school building was like a palace to them because it had electric lighting. They lived fairly isolated lives, and had not experienced meeting and talking about ideas with other people their own age outside their own families. They sang and had dances, which they called “musical games” because the Baptists would get upset about dancing. Many romances began here and people got married; it was really wonderful.

What kind of a teacher was Murray?

She was a great carver, but also very humble. She would sit with them and help them carve with skill and feeling. She said, “If you strive for excellence it will be well received in the marketplace. Make that rabbit look like it is just taking a breath and about to take another one.” She’d bring a live pig or rooster and set it on the table as a model. My friend Hope told me when she was carving the babe in the manger for a crèche scene Murray said, “You’re going to have to have another baby, because the face on this looks too adult.”

Mary Doornbos manages the Folk School Craft Shop (800-365-5724) at the John C. Campbell Folk School in Brasstown, NC. For more information about programs at John C. Campbell Folk School, see folkschool.org.

Fantastic information, what a rich history of the arts and carving, thank you so much for sharing!