Portrait by Lauren Rutten

When Nina Kawar’s marriage ended in divorce, she helped herself heal from that painful experience by falling in love again — with sculptural ceramics. During that difficult transition, she took an evaluative test, the kind that identifies particular aptitudes and proclivities. The results all pointed to a career in art, which was just the encouragement she needed. At age 27, Kawar, who grew up in a Palestinian American home in Wisconsin, began pursuing a BFA at UW-Oshkosh.

“I decided, this is what I want to do, because when I’m doing art, my heart is happy. I go to another place, a space of connecting with my higher self and following my intuition,” she says. She subsequently earned a Masters of Fine Arts in Ceramics at Clemson University, and “a year into grad school, I fell in love with porcelain.”

Porcelain is derived from a silicate substance that typically comes from the highest reaches of mountains, where it hasn’t collected any other significant mineral deposits, says Kawar. That contributes to its purity and rarity, and makes it more expensive than other clays. Porcelain clay was originally mined and developed in China, but it also exists in the mountains of Western North Carolina.

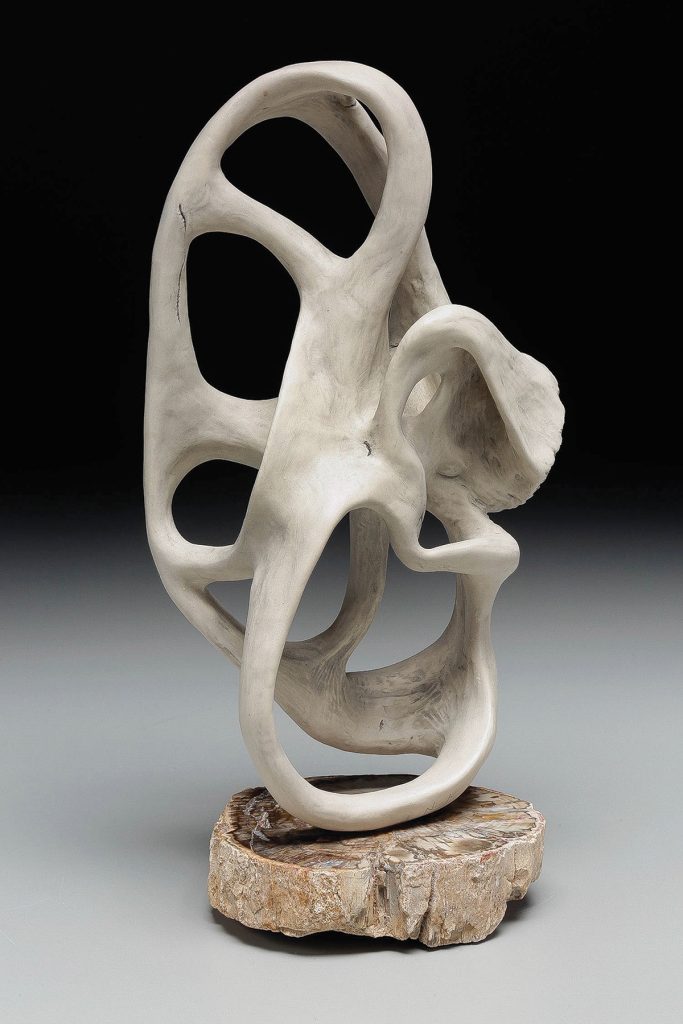

It’s a medium loaded with paradox. Ask it to exhibit good posture or maintain a desired shape and it may instead slouch, slump, or warp. Finished pieces can be translucently thin — thus porcelain’s reputation for fragility.

But porcelain is also extremely hard and nonporous (which is why it’s prized for high-end dental veneers and tile floors). And the medium’s unusual complexities make it the ideal match for Kawar, both physically and philosophically. “What I’m speaking to in my work is fragility and temporality, but also resilience — and porcelain is very strong, like ourselves. I have multiple bodies of work that are expressions of the human condition — not only about pain and healing, but also transformation and transcendence.”

An interest in biology, environmental science, and metaphysics recently led her to an in-depth exploration of mushrooms and fungi. “I saw the movie Fantastic Fungi, which brings awareness to [mushrooms’] ability to heal. That lit a fire under me. Mushrooms have symbiotic relationships with other species, and I truly believe they can help us save the planet.”

Her belief is shared by scientists who have found that, among other phenomena, mushrooms break down molecules of organic matter and build nutrient-rich soil that retains moisture more effectively. The enzymes exuded from mushroom mycelia make minerals locked within rocks more accessible, and can even help to ward-off some microbial pathogens.

“I’m still learning the language of mushrooms and this new body of work,” Kawar says. “It’s my first representational art. I’m even introducing color to my work. I’m so excited that it makes me emotional to talk about it — it feels like I’m falling in love.”

Nina Kawar, Marshall. The artist is represented by Flow Gallery (14 Main St., Marshall, flowmarshall.com) and Woodlands Gallery (419 Main St., Hendersonville, woodlandsgallerync.com). Her work will be shown at Blue Spiral 1 (38 Biltmore Ave., Asheville, bluespiral1.com) in the exhibit Finding Nature, opening Friday, May 7 and running through Friday, June 25. For more information, visit ninakawar.com, pure-ritual.com, and on Instagram: @ninakawar.