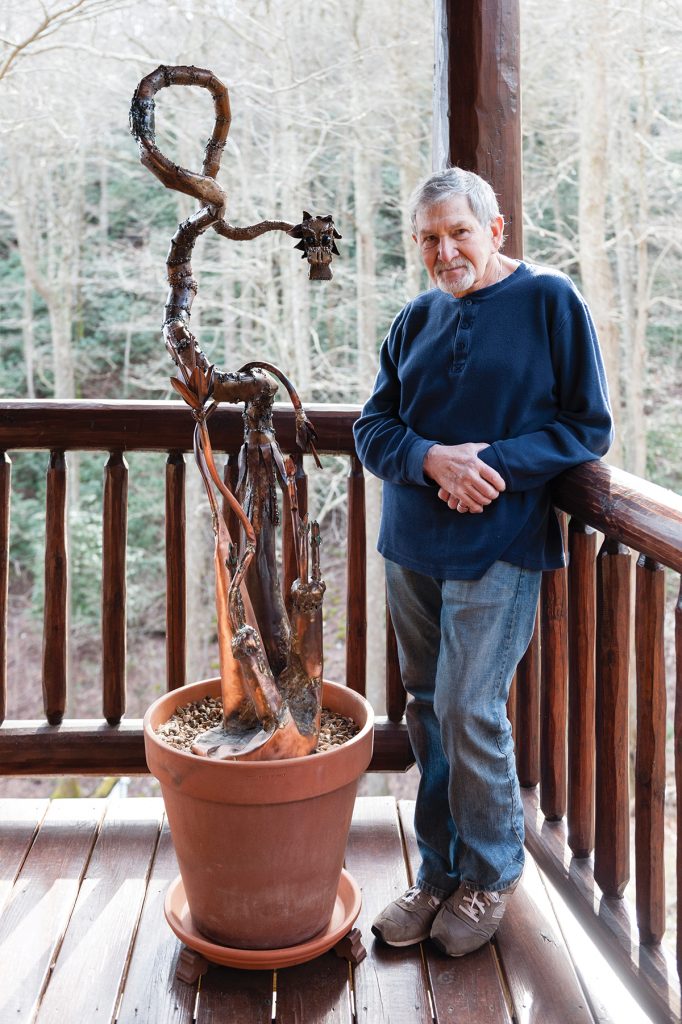

Peter Dallos says the pandemic freed his artistic vision.

Portrait by Lauren Rutten

When Peter Dallos made his first metal sculpture, in 1998, the work’s welded and coruscated steel, battered but resilient, seemed to crystallize much of his personal history. A two-foot-tall, botanically inspired creation whose branches swell into flower-like forms, it was one of the first pieces in what became a series pointedly named Struggle, with its emotional roots in Dallos’ escape from his native Hungary 40 years earlier, after Soviet troops had crushed the country’s brief restoration of democratic rule.

“I initially conceived the work as representing conflict between Western civilization and its adversaries,” Dallos says of the series, which now numbers nearly 50 pieces exploring not only political repression but other challenges to humanity, such as climate change. Later works in the series suggest a rebellious Earth taking revenge on its human tormentors. “The actual political interpretation of the work emerged as the series began,” Dallos notes. “I just enjoyed the juxtaposition and interaction of manmade and organic elements.” The most autobiographical of his work is his War series, now in the permanent collection of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington.

Photo by Lauren Rutten

Trained in both the arts and sciences while growing up in Budapest, Dallos eventually found his way to Chicago and a long career at Northwestern University as an internationally recognized neuroscientist in charge of a major research laboratory. (He is the school’s John Evans Professor of Neuroscience Emeritus.)

But giving shape to his experiences confronting conflict was never far from his mind, leading to those first works in the Struggle series while still meeting his university responsibilities. Retiring from his science career nine years ago, Dallos settled in Marshall and turned his attention full time to making art.

Photo by Lauren Rutten

“I didn’t just retire from something but to something,” he points out. “A second career in sculpting.”

Joining the Struggle series are other works that are more indirect in their commentary on social issues, but no less striking. The End of the Road series — complex architectural pieces portraying mortality as the insurmountable obstacle confronting the individual — transitions to later machine assemblages and delicate nature studies, combining both manmade and organic materials in subtle conversation.

Photo by Lauren Rutten

“The first two series were dark and foreboding,” Dallos observes, “expressing humanity’s problems and the sense of impending personal mortality. But the Machines series has no message. It just comprises small, nonfunctional machines simply to explore the beauty of this human construct.”

Similarly, a collection of re-imagined candlesticks plays with form versus function, and a group of purely sculptural forms can be admired simply for their imaginative shapes and workmanship.

Photo by Lauren Rutten

A new creative direction takes the form of surface-colored orchids nesting in ceramic pots, whose beauty and delicacy are their only message. “Maybe as I enter old-manhood, I have finally learned to worry about the moment, not the ‘Big Picture,’” Dallos admits.

It’s a perspective no doubt influenced by a year of pandemic isolation. “My vision has become lighter,” the sculptor says, “and, paradoxically, I’m now divorced from responding to the world’s problems, as worse and more monumental as they may become.”

Peter Dallos, Marshall. For more information, see pdallosart.com.