Portrait by Colby Rabon

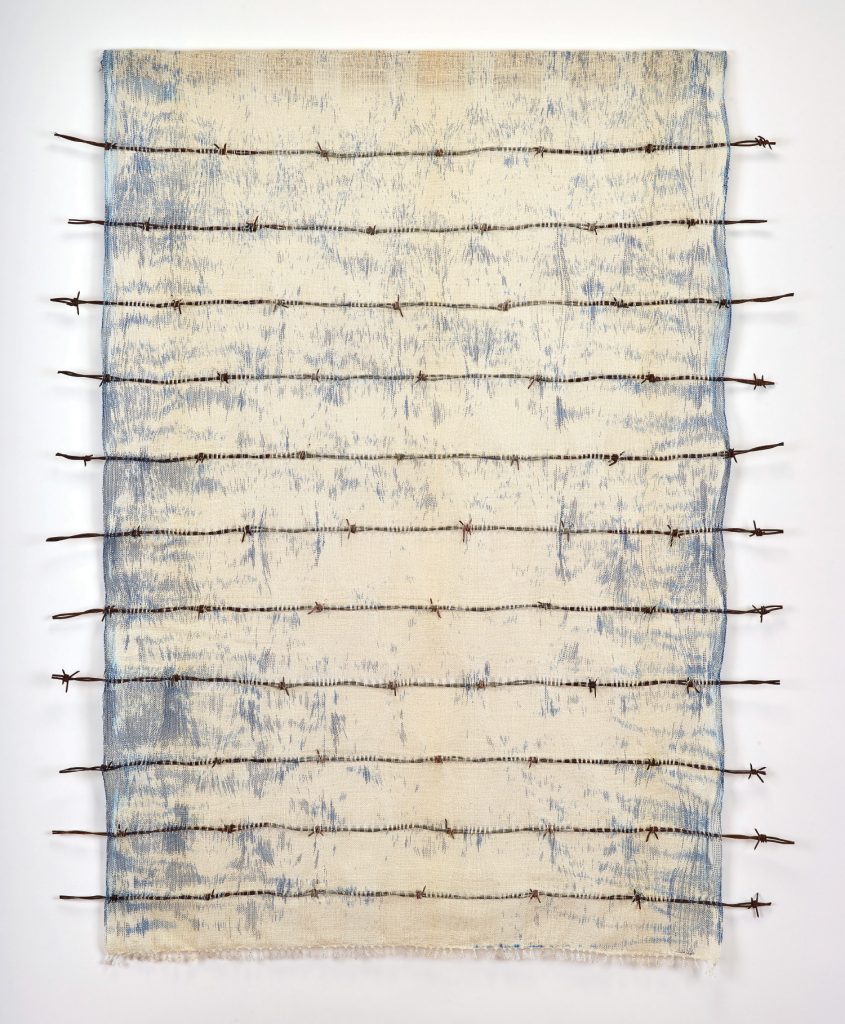

Textile artist Amy Putansu says her earliest “fiber memory” is watching her fisherman father using a knotted netting technique to knit heads for his lobster traps. Recently, she learned how to make netting herself, and is now incorporating it into her newest work. She considers it a symbol uniting culture and industry — “a meditation on our relationship with food and nature.”

Putansu grew up in Clark Island, on the coast of Maine, and went on to the esteemed Rhode Island School of Design to study painting. “I took an elective in fabric silkscreen my freshman year. It was interesting, akin to painting…” But when she was introduced to weaving, she says everything fell into place. She declared her major in textile design. “I was crystal clear it would be my life pursuit.”

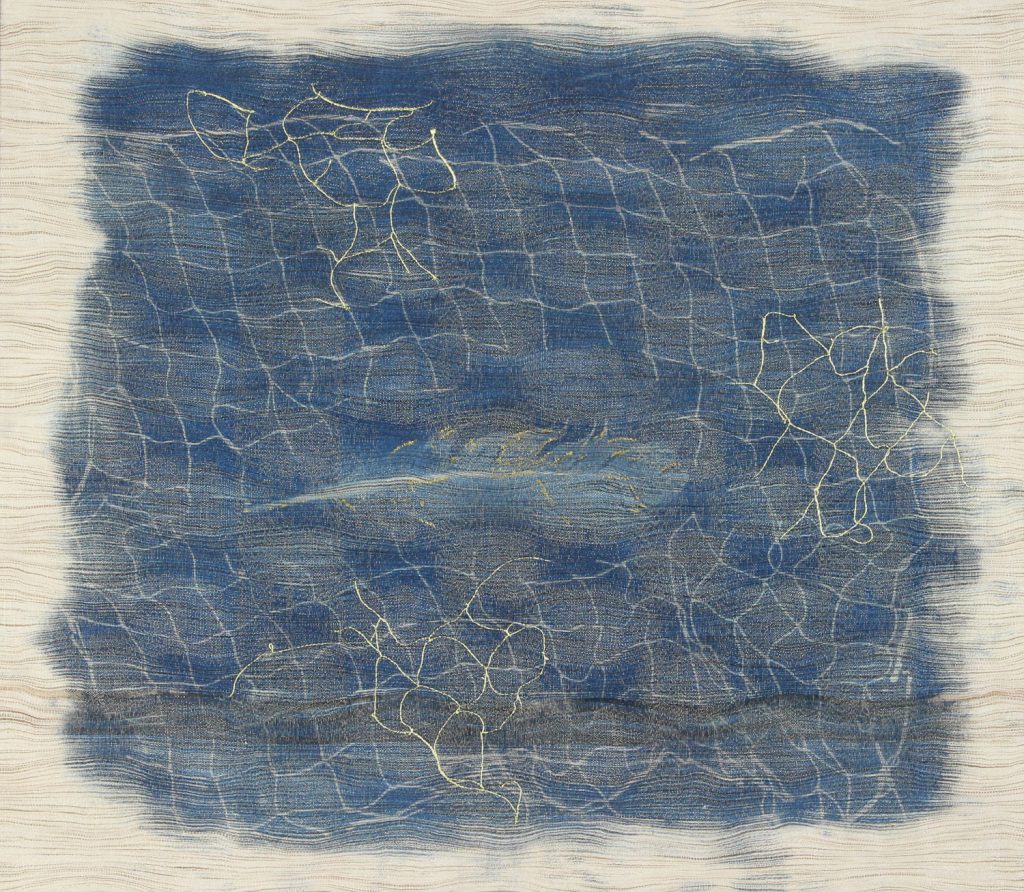

Given her highly trained background, Putansu can effortlessly compare mediums. “Painting is largely a surface technique — color, line, and shape are added to an existing substrate. Weaving is the substrate,” she explains. “Through my recent work, I combine both approaches holistically. As I build the ‘canvas’ with hand weaving, I am also building the wall piece. … Line is created with woven or stitched thread, and color is achieved by choosing the appropriate dye for the fiber.”

But unlike painting, perhaps, her style of weaving can be “incredibly exacting.” Putansu reveals that “every single thread” in the structure of her object is handled multiple times. Before the creative process begins is a phase of “extensive planning and organization.”

Once the project is underway, the physical nature of weaving becomes a kind of emotional outlet. “It’s an active process … [and] throwing the shuttle can be quite meditative. It reminds me of activities like cross-country skiing — a series of repeated movements that create a certain flow.”

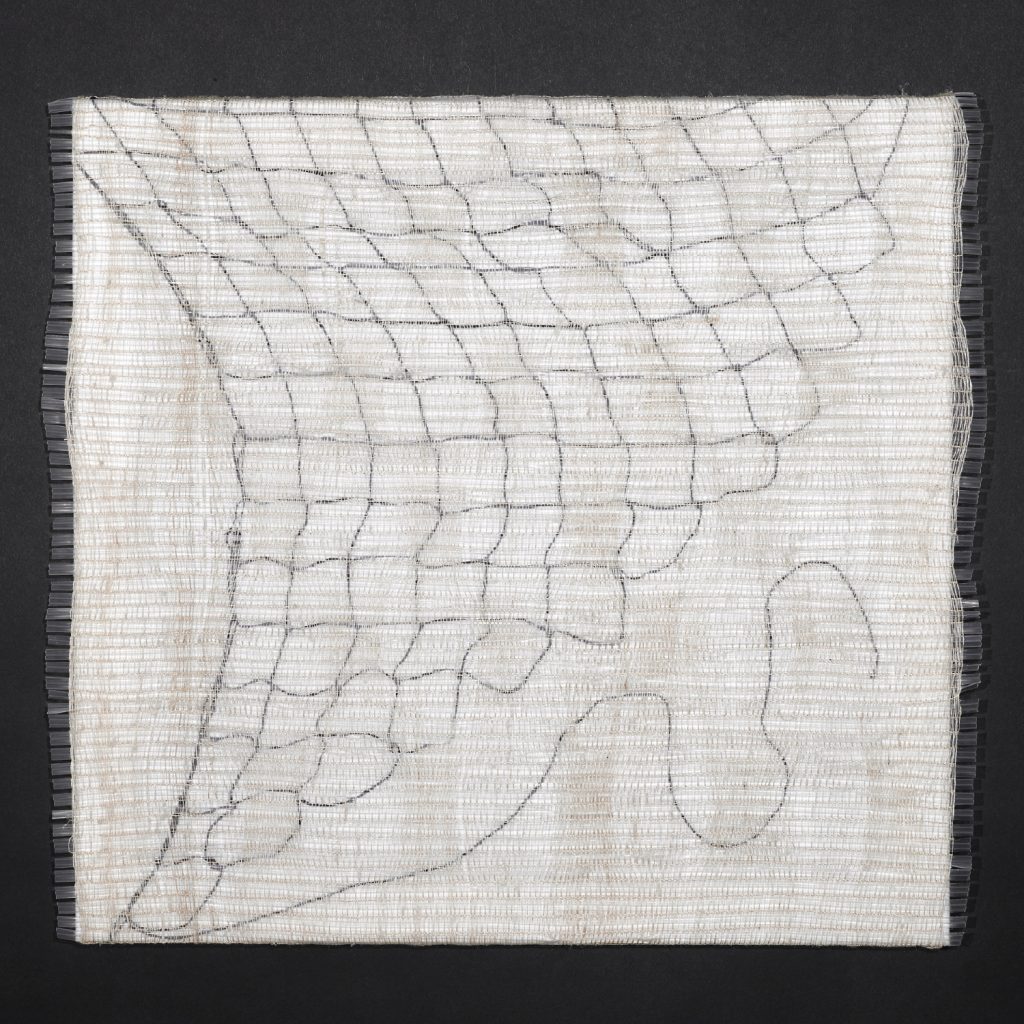

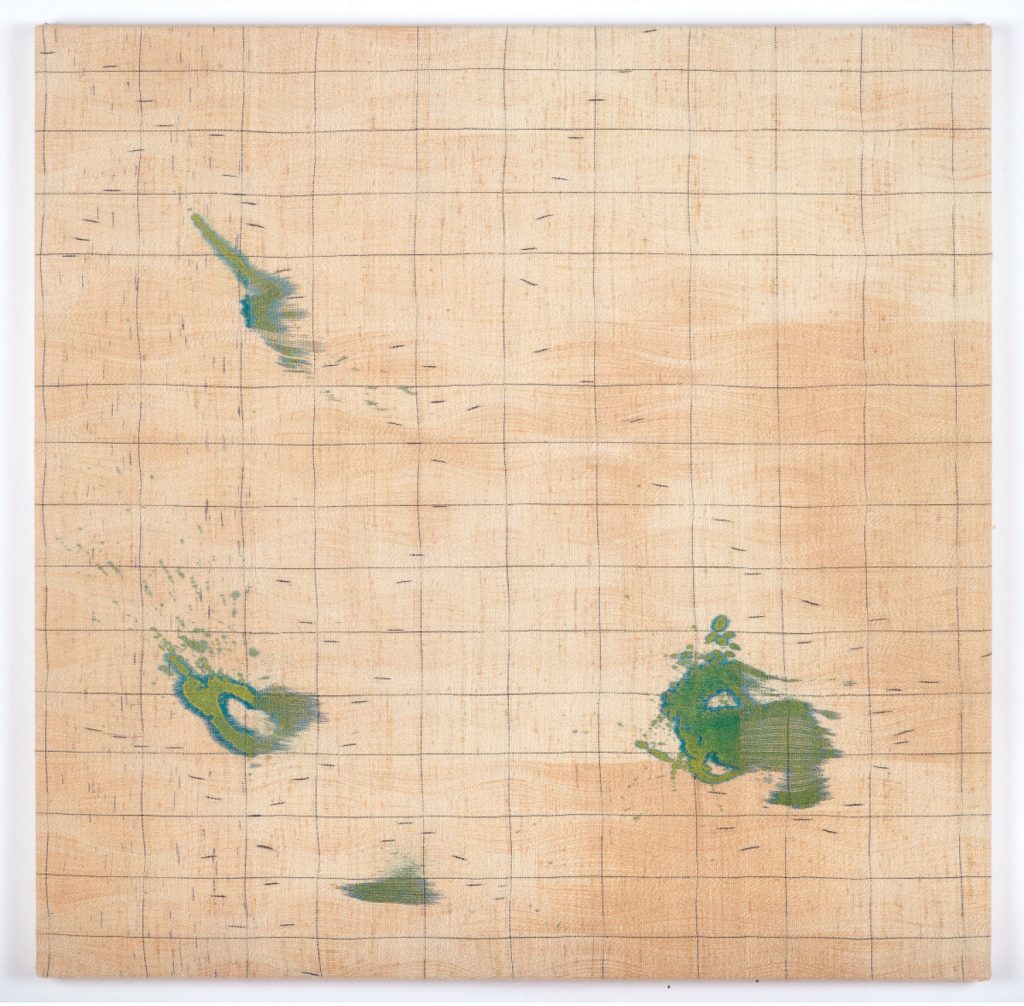

Her body of work titled Disappearing Islands borrows from lines found in nautical navigational charts. Putansu describes Contours, the most ambitious piece of the series: “Having transferred linework from a chart of the Gulf of Maine onto taut, unwoven warp thread on the loom, those threads are then woven using the ondulé method of distorting those lines, and finally hand stitched with embroidery techniques on the woven cloth.” (Instead of the traditional woven grid, in the complex ondulé technique, one set of thread is maneuvered to form curves — what Putansu calls “sinuous lines.”)

The weaver moved to Western North Carolina in 2008 to accept a position leading the fiber curriculum of the Professional Crafts Program at Haywood Community College, where she still teaches. She loves her home in the mountains and is grateful for all the support that crafts get here, though the rugged Maine coast and the many moods of the ocean continue to influence much of her work.

“I have been drawing upon that influence to address existential questions such as life, death, and impermanence, what defines a culture, and spiritual examination. It happens to be my language of choice because it’s what I know and what is personal to me.”

Amy Putansu, Clyde, Haywood County. The artist’s work is on display at Blue Spiral 1 (38 Biltmore Ave., Asheville, bluespiral1.com). Putansu will teach an ondulé workshop, “Weaving Waves,” at Penland School of Craft from Sunday, July 21 to Tuesday, Aug. 6 (penland.org). For more information about the artist, see putansutextiles.com.

Beautiful work.