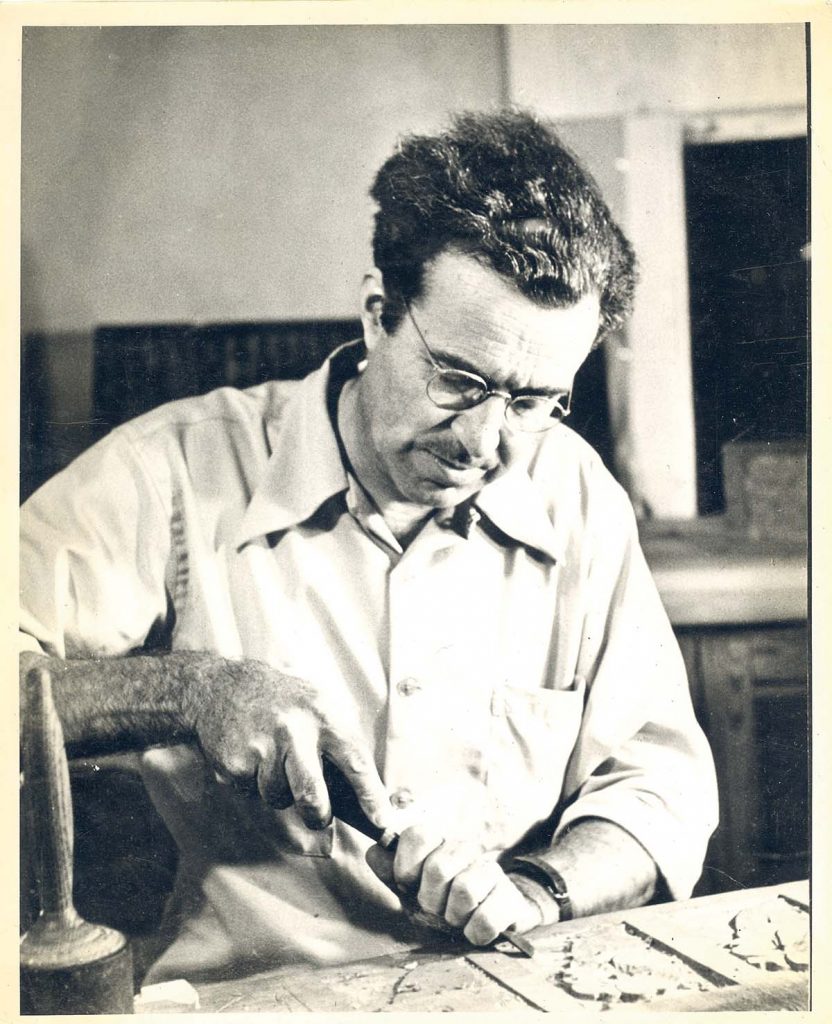

Hardy Davidson, whose ancestors settled in WNC around the time of the Revolutionary War, was a mostly self-taught woodcarving artist born in 1900. He is especially known for his colorful ducks, designed to be displayed on a wall. Although Davidson rarely traveled outside of his native Swannanoa Valley, his mallards flew off the shelves in northern metropolitan shops and craft galleries. They migrated into national magazines like House & Garden, and eventually nested in private European collections.

“Hardy knew how to market himself,” confirms Glenn Cox, his great-nephew, who is Vice President of Administration at Explore Asheville Convention & Visitors Bureau. “A cousin of mine was in New York City at an attorney’s office and there they were: Hardy’s ducks on the wall. My mom still has a copy of Esquire from the ’40s or whenever, with his ducks in it. They were part of a big magazine foldout called ‘Gifts for the Man in Your Life.’”

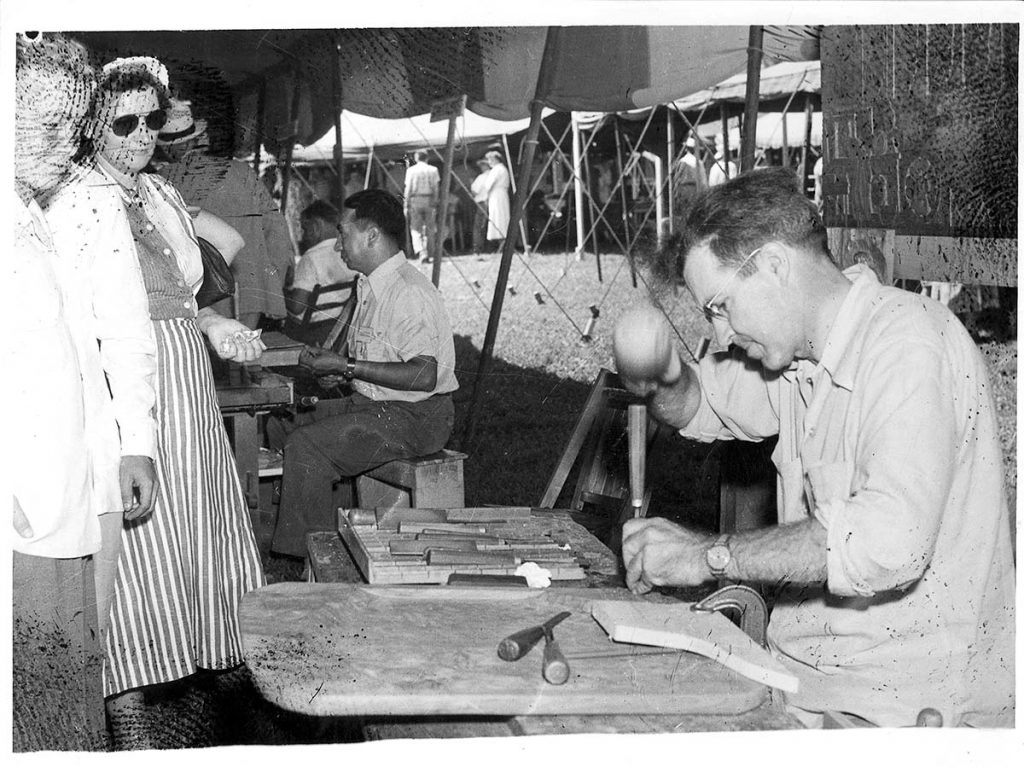

Davidson sold his ducks, a few other birds like cardinals, and some furniture through the Southern Highland Craft Guild, of which he was an early member. Occasionally he’d carve figures of mountain people, and he once sold a carving of a piano player and orchestra conductor to a collector in France. But mostly he dealt in ducks, admittedly for pragmatic reasons: He could carve one in an hour or less and paint it in 10 or 15 minutes. That productivity enabled him to make woodcarving a profitable entrepreneurial enterprise.

“He made what I assume to be more than a thousand of them,” Cox says. “All were made in three parts — the body, the front wing, and the back wing. He used a proprietary paint out of pastels and oils of some sort, and I don’t think he ever told anyone the recipe. But the colors on the ducks never fade, even ones he made 70 years ago.”

He also carved his own violin and taught himself to play it. “Hardy had a really squeaky, high-pitched voice,” recalls Cox. “When he played his violin it sounded like his voice, but he didn’t mind.”

Cox, although not an artist or craftsman by trade, came to WNC in 2001 to support and promote the craft industry as the Executive Director of Handmade in America, an organization devoted to economic development in rural WNC. One way that his great-uncle supported the local craft community was by teaching woodworking at Warren Wilson College. “He was a smart guy,” Cox says. “I’d go to his house as a kid and he’d be reading The New York Times, while listening to classical music on old 78s.” The youngest child in his family, Davidson lived through the devastating Asheville flood of 1916 and survived the pandemic of 1918. He didn’t fare so well, however, when a squabble broke out at the dinner table.

“When Hardy was young he and his siblings starting fighting at the dinner table. I don’t know what the argument was about, maybe over who got the last piece of fried chicken. But anyway, Hardy had a fork in his hand and while they were fighting, he accidentally poked his own eye out. To me what’s amazing is that he could make such detailed 3-D art, carving with only one eye.”

The monthly Craft Legacy Series of articles leads up to American Craft Week, a national celebration highlighting objects handmade in the U.S. Artists, galleries, museums, festivals, craft schools, and statewide tours participate with public events from Friday, Oct. 2 through Sunday, Oct. 11. This 10-day “week” is full of activities large and small, hosted by individuals and large organizations. As a major craft center, Western North Carolina will offer a wide variety of happenings. Learn more at americancraftweek.com.

I am attempting to determine when Hardy Davidson died, as he learned the craft of woodcarving from The Artisans’ Shop in Biltmore Forest in the 1930s. This is for my forthcoming book on Eleanor Vance, Charlotte Yale, and Biltmore Industries. Thanks – bruce johnson

Bruce, Hardy Davidson died in August 1981. His obituary can be found on Newspapers.com. He was born in 1900.