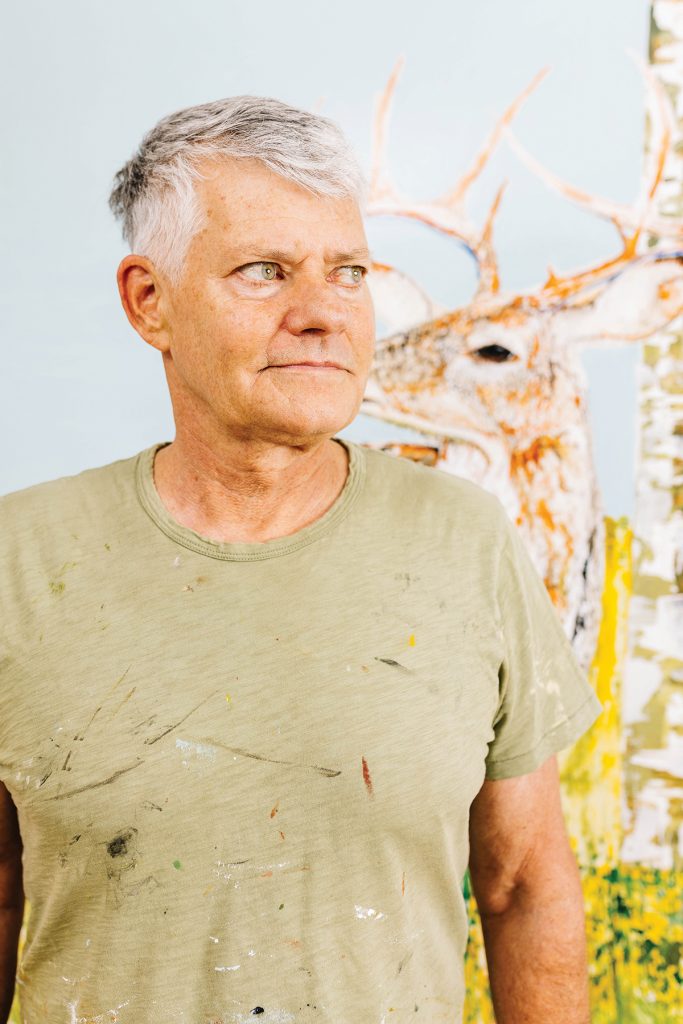

Portrait by Evan Anderson

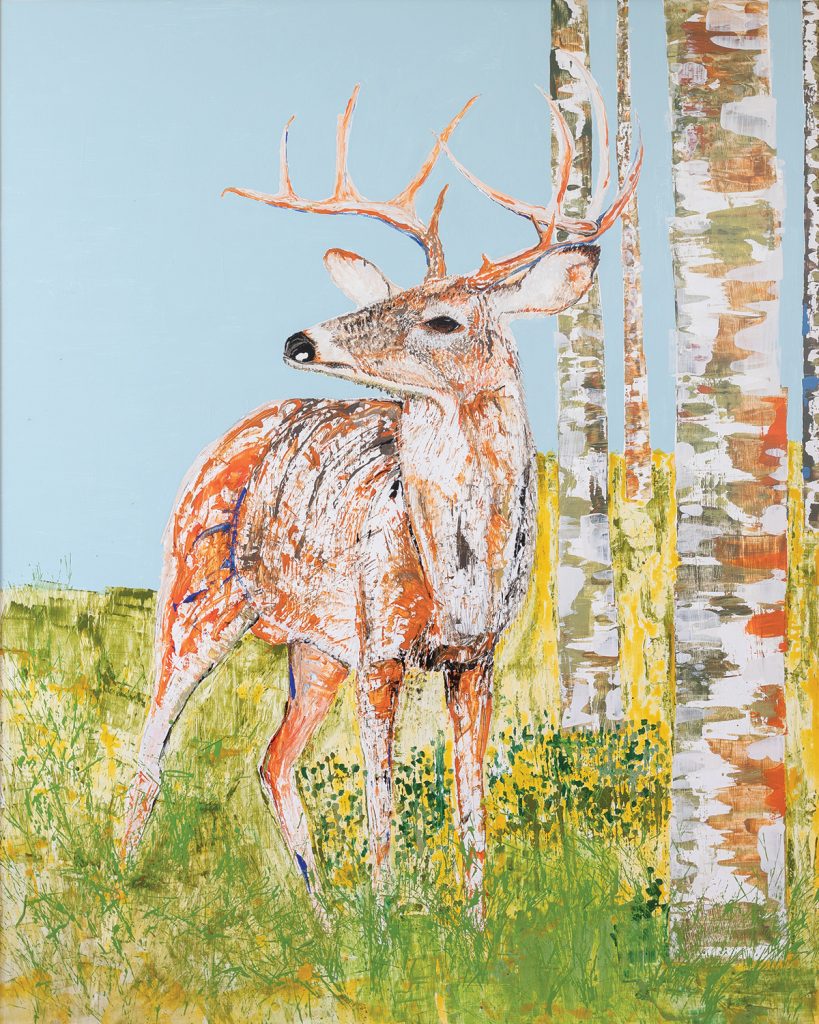

The eyes of the animals in Jackson Hammack’s paintings don’t blink. They stare straight at you, even through you, as though to say, “I am in my element; what are you doing here?”

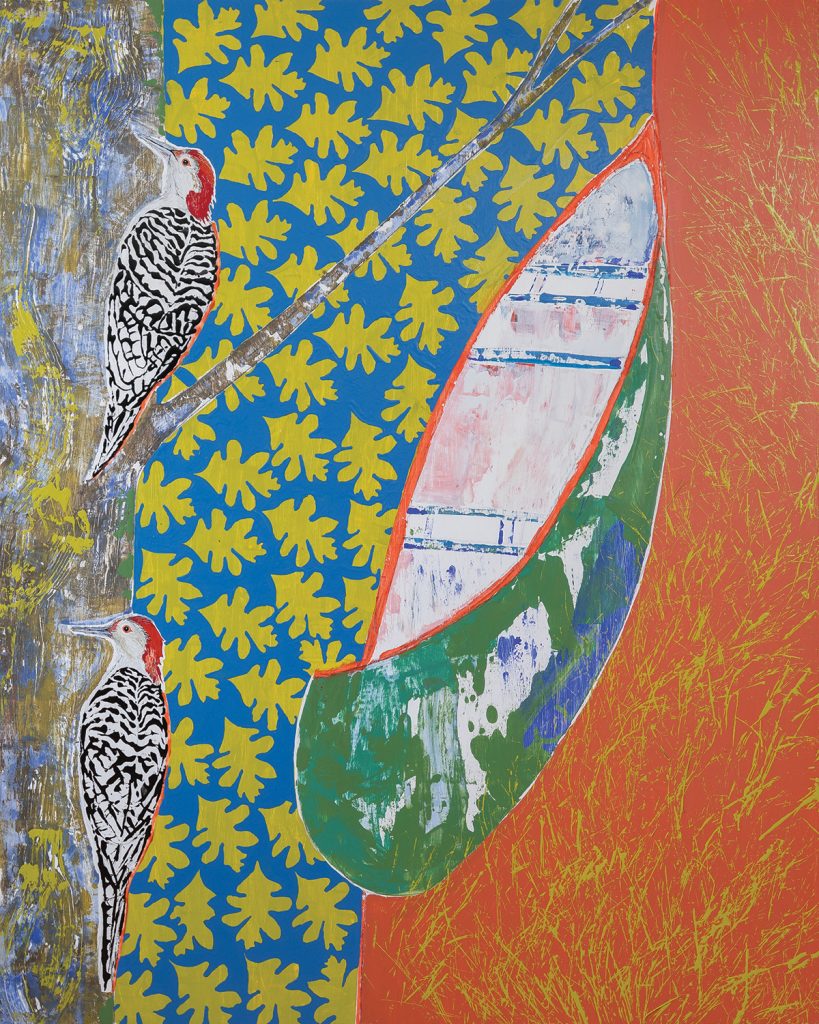

Depending on where the self-taught artist is living — right now it’s Black Mountain — the animals might be bears, deer, woodpeckers, or owls. When Hammack lived in Texas, roadrunners showed up. Now that he has a second home in Georgia, he’s wondering what coastal creatures might find their way to his canvases, which are usually large boards.

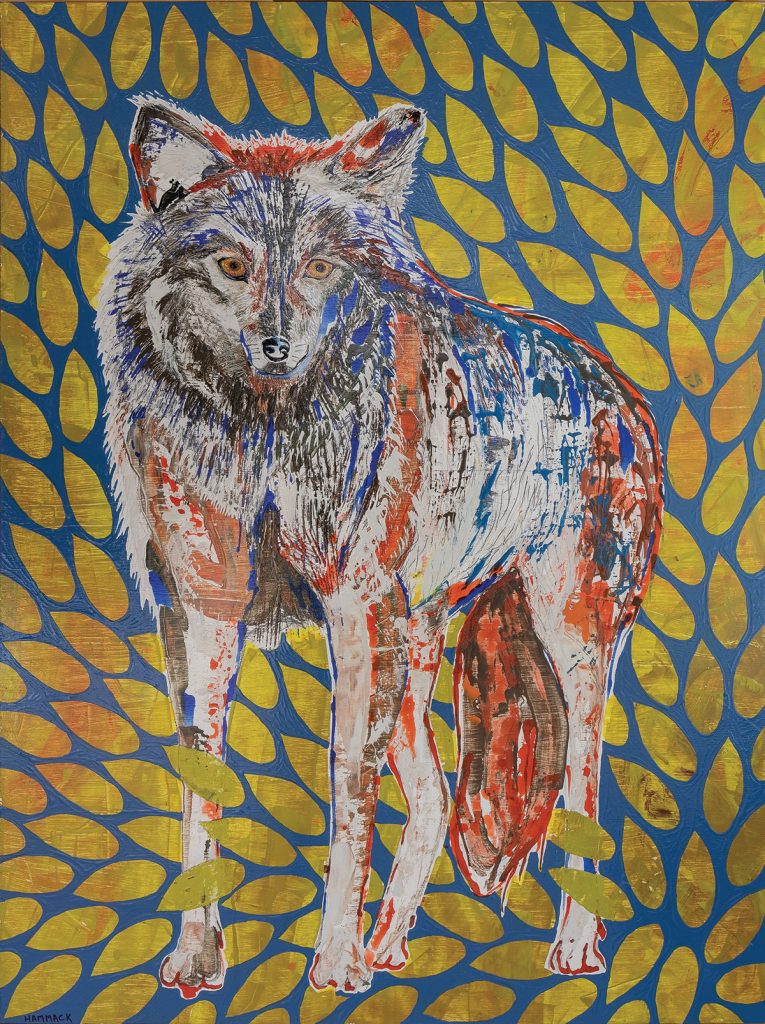

The abstract, colorful, and often lone animal is set either against a bold, glossy, solid background or in front of a pattern of contrasting leaves. The work is contemporary and masculine, with traces of wood engraving, and the compositions are almost always sparse, simple, and demanding of the viewer’s attention.

“I like to keep the background simple to focus on the essence of the animal or human,” explains Hammack, who refers to himself as the Andy Warhol of the natural world. “What we share with other living creatures is the wonderment of creation. We can recognize this when we look someone ‘straight in the eyes.’ We rarely have this opportunity in the wild.

“My paintings allow you to look straight into the eyes of a bird, or bear, or deer, and connect with this communal life force. When I first apply paint to one of my large canvases, I start with the eyes of the animal. This may seem odd — to do such a small-detail work firsthand.

“But if I cannot capture the bird or animal’s life force from the beginning, no amount of other work on the canvas will matter. ”

Since his early childhood, Hammack has painted. At times, after work, he would paint in a friend’s hot attic, laying large canvases on the attic floor, something he still does so he can puddle paints to build layers. He uses pencils, brushes, sticks, and grass to move the latex, oil, and house paints. At 65 years old, he is now totally committed to his art and has produced nearly 150 paintings since he retired two-and-a-half years ago. For 22 years, he worked in the airline industry “on the ramp” and as a flight attendant. He then spent 10 years as a building contractor. Along the way, he always painted, and has long been represented by the Craighead Green Gallery in Dallas, where he has an exhibit beginning in May. His work has been available through The Lucy Clark Gallery & Studio in Brevard for only the past few months, but has already found many places to hang in mountain homes.

“My first visit to Asheville was almost 30 years ago,” Hammack reflects. “I absolutely and instantly felt a connection to the area. It felt familiar, as if I had lived there before. We bought a lot and built a cabin in Black Mountain two year later, and dreamed about moving there permanently — and two-and-a-half years ago did just that.

“Art is fluid and ever changing with me. We recently bought a loft in historic Savannah, and I can feel a change coming on with the different wildlife, as well as a more urban experience of human activity. Stay tuned.”

Jackson Hammack, Ravenscroft Studios, Black Mountain, jacksonhammackart.com. Hammack is represented by The Lucy Clark Gallery & Studio (51 West Main St., Brevard, 828-884-5151, lucyclarkgallery.com). His work is also sold at Marquee Asheville (36 Foundy St. in the River Arts District, Asheville, marqueeasheville.com).