Mission Hospital’s North Tower, a $400 million addition completed in October 2019, is home to multiple units, including the facility’s Pulmonary ICU. The pandemic hit a volatile crescendo on Jan. 16 of this year, and of the 175 COVID patients in Mission’s six-hospital system, 133 of them battled the virus here, and some lost their lives.

But the North Tower sees beauty as well as sadness, thanks to the nearly 160 regional artists from the health system’s 18-county service area whose works adorn the inside of the 12-floor structure.

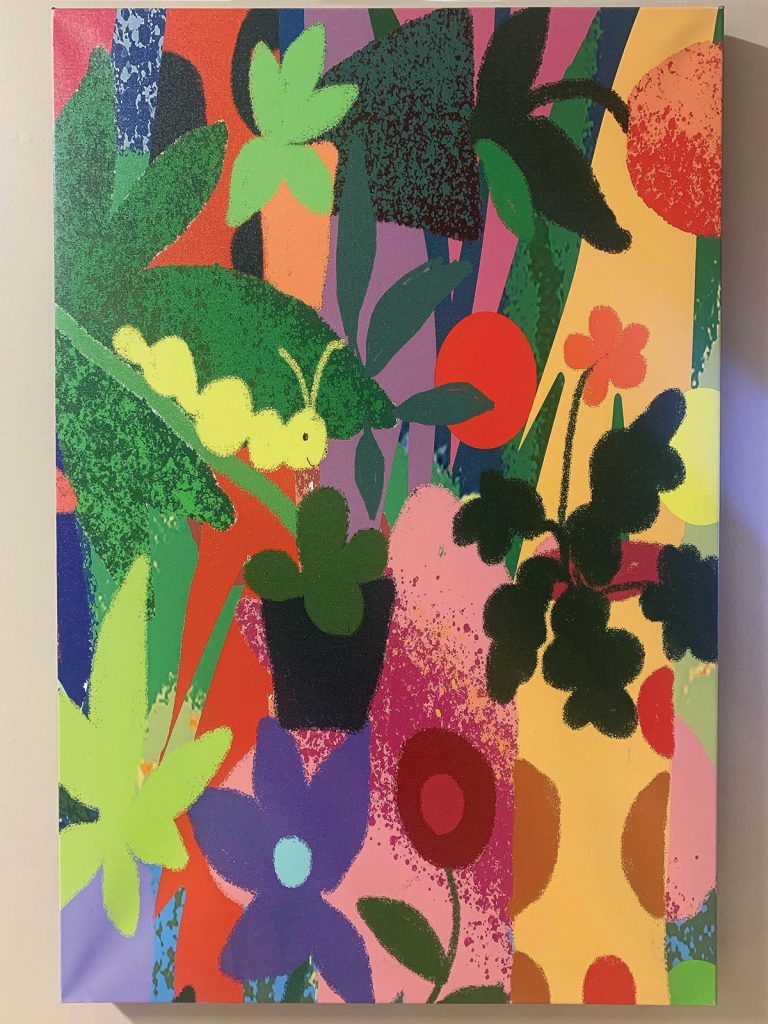

Walking inside the 630,000-square-foot building on Biltmore Avenue feels more like entering an art museum than a medical facility. Art is, quite literally, everywhere. In August 2018, Mission issued a call for submissions of 2D and 3D work that emphasized “nature and/or culture.” Some 659 pieces were later selected and commissioned, giving rise to what is thought to be the largest collection of local art in a North Carolina hospital. The vast lineup features emerging and established artists in mediums that span painting, photography, sculpture, ceramics, textiles, encaustic, glass, metal, and origami.

“We wanted to bring more of a feeling of community and home inside the hospital,” says Nancy Lindell, Mission’s director of public and media relations, during a tour of the North Tower’s main lobby. Positioned near the registration desk, Kenn Kotara’s Land of the Noonday Sun immediately commands attention. The piece is made from copper with verdigris patina and hand-hammered Braille. The bluish-green patina flows across the panels organically, mirroring the Nantahala River, while the Braille resembles meandering tributaries.

In November 2019, the hospital hosted The Art of Caring, a reception during which community members could view the public works installed in the North Tower, by Kotara and other high-profile local artists such as Lara Nguyen, an art professor at Warren Wilson College. Since then, though, pieces in the common areas have gone largely unseen due to visitor restrictions. Even fewer people have seen the artwork sequestered in more private areas of the hospital, such as Becca Allen’s landscape painting in the Intensive Care Unit waiting room.

A mountain scene awash in verdant greens and smoky blues, Calling Me Home intends to ground patients by evoking a sense of place. “When you are stuck in a hospital room, it’s a nice reminder that there is something else out there,” Allen says. “Art provides a connection to the outside world.”

As an art therapist, Allen is well versed in the mental-health benefits of creative expression. For the creator, art can be a “link to the subconscious” or a communication tool that helps people externalize what’s hard to say aloud. But there are benefits for the viewer, as well. According to a 2010 study conducted in three Scotland hospitals, simply looking at an appealing painting can shorten the length of a patient’s stay, increase pain tolerance, and decrease anxiety. In other words, art can be medicine.

“If patients have this one constant, beautiful thing in their room, they can count on it when they’re in pain or when they really miss their family,” says Allen. “That’s especially important right now.”

Holly McGee, an Asheville-based illustrator whose pieces Yellow Friend and Dog and Bird are located in the North Tower’s 12-bed pediatric emergency room, echoes these sentiments. She believes the art endeavor has the potential to not only redefine the patient experience, but also how many people think about hospitals.

“Antipathy toward hospitals is perfectly natural — these are places that house the ill, injured, or grieving,” notes McGee. “But they are also places of healing and life-changing moments — [including] the reunion of family members and friends.”

Art programs such as the one at Mission have the potential to “help people see and feel about hospitals in a new way,” she adds.

In times of COVID-19, when medical facilities are perceived both as safe havens and as places of immense danger, a shift in perspective can go a long way. But what happens when the workers inside — the countless nurses, doctors, therapists, social workers, janitors, and dietary aides — need some perspective, too?

“Staff have been working hard around the clock. It’s tiring to see people so sick. It’s tiring to see people not recover. It’s tiring to care for so many patients,” says Lindell.

But art can help, says Amy Waters, a Child Life Specialist with Mission Children’s Hospital.

“The artwork has been such a comfort,” she says. “I specifically remember walking into work and feeling something was out of place [in the pediatric emergency department] because the bird painting I was used to seeing each morning wasn’t there. I found out a few moments later it had been moved just a little down the hall. Now the wall is complete with tons of color and happiness.”