Portrait by Jack Robert

“Sometimes unexpected things happen, and I have to work around it. You might come into some cracks or a hole and it’s, ‘Oh, didn’t see that coming.’”

Aaron Iaquinto is talking about working with a piece of wood — but he could also be narrating his artistic path, one that’s brought him growing recognition creating one-of-a-kind spoons with poetic names like “On Reason and Passion,” “On Joy and Sorrow,” and “The Coming of the Ship.”

His curiosity about his chosen material began in middle school, exploring the forest behind his home in New York State. “I got a hatchet and would cut dead trees with no real intention,” he recalls. “I dragged one big piece out of the woods thinking I would make a totem pole, but I didn’t have the tools.”

His love of photography — particularly shooting nature — brought him to East Carolina University’s arts program, but he lost interest as film transitioned to digital. Instead, he found himself hanging around the wood shop. “I felt that tactile world again, doing things with my hands, and it felt right.” He wanted to make acoustic stringed instruments, but just as his first semester in wood design was set to begin, the head of the program retired.

“The school promised us they would hire a new professor to lead the wood concentration — but never did,” he notes. Instead, the shop tech taught him how to use the tools, and he carried on what he describes as “independent study,” dipping into the small-metals jewelry department. “The professor there helped me hone my craft in a different medium and bring that to what I was doing with wood.”

But it was studying abroad in India that had the most significant impact on Iaquinto’s direction. On his final of several trips, he remained there for an additional three weeks, doing a woodcarving workshop at Norbulingka, a Tibetan-heritage preservation school.

“The instructor spoke no English, so he would show me something, then I would do it,” recalls Iaquinto. “He would say ‘no no’ or ‘yes yes.’ It worked out.”

Photo by Jack Robert

Back in the States, Iaquinto joined his bluegrass-musician brother in Asheville, working for five years at the Old Wood Company until it closed shop. He had already started making spoons, though he says he gave away more than he sold. “Not very lucrative,” he admits with a laugh. But he loved the process, finding it very meditative and creatively exciting. A friend who works at Grovewood Gallery suggested an exhibition devoted to spoons, which turned into Spoonin’ in 2019.

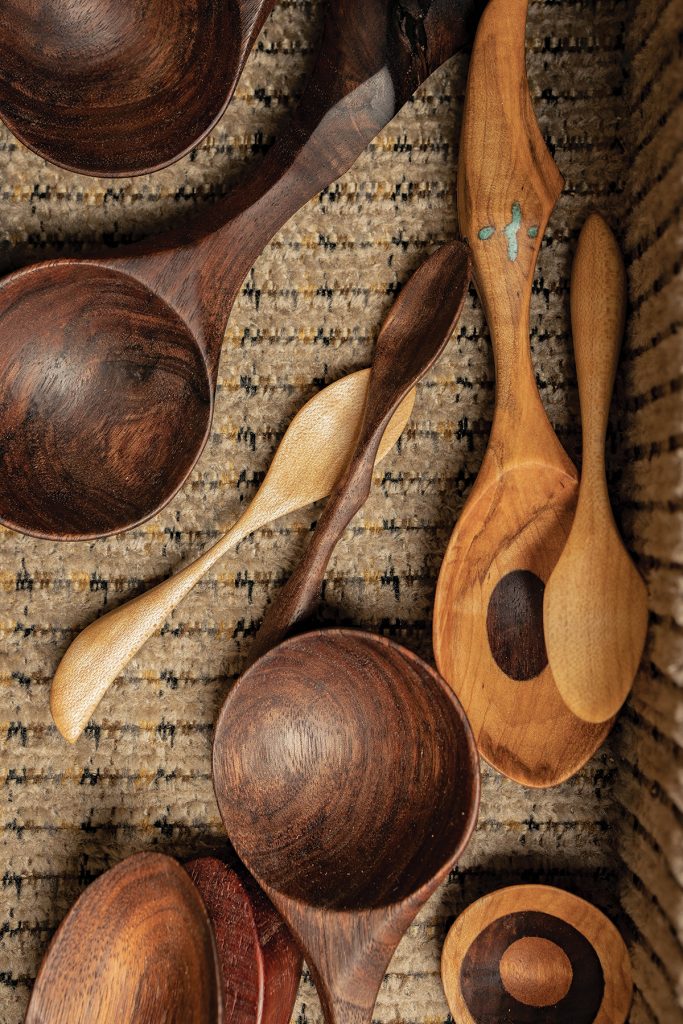

“My goal is to elevate the object,” Iaquinto explains. “Serving spoons are about community, serving people or passing a big bowl with a spoon. The spoon is utilitarian, but I wanted to push it to a piece of art. Mine are both.”

Iaquinto’s spoons all begin with hand tools and a block of wood — typically scraps of black walnut, mahogany, oak, maple, and cherry, plus some exotic species like black ebony for inlay. Then the improv kicks in. “I have ideas going in, but different things happen and sometimes it ends up not even close to what I was thinking. It becomes what it’s meant to be.”

Aaron Iaquinto, Asheville. Iaquinto sells his spoons at Grovewood Gallery (111 Grovewood Road, Suite 2, grovewood.com) and at the gallery at Foundation Woodworks (17 Foundy St., foundationwoodworks.com). For more information, see aaroniaquinto.com.