Portrait by Pat Barcas

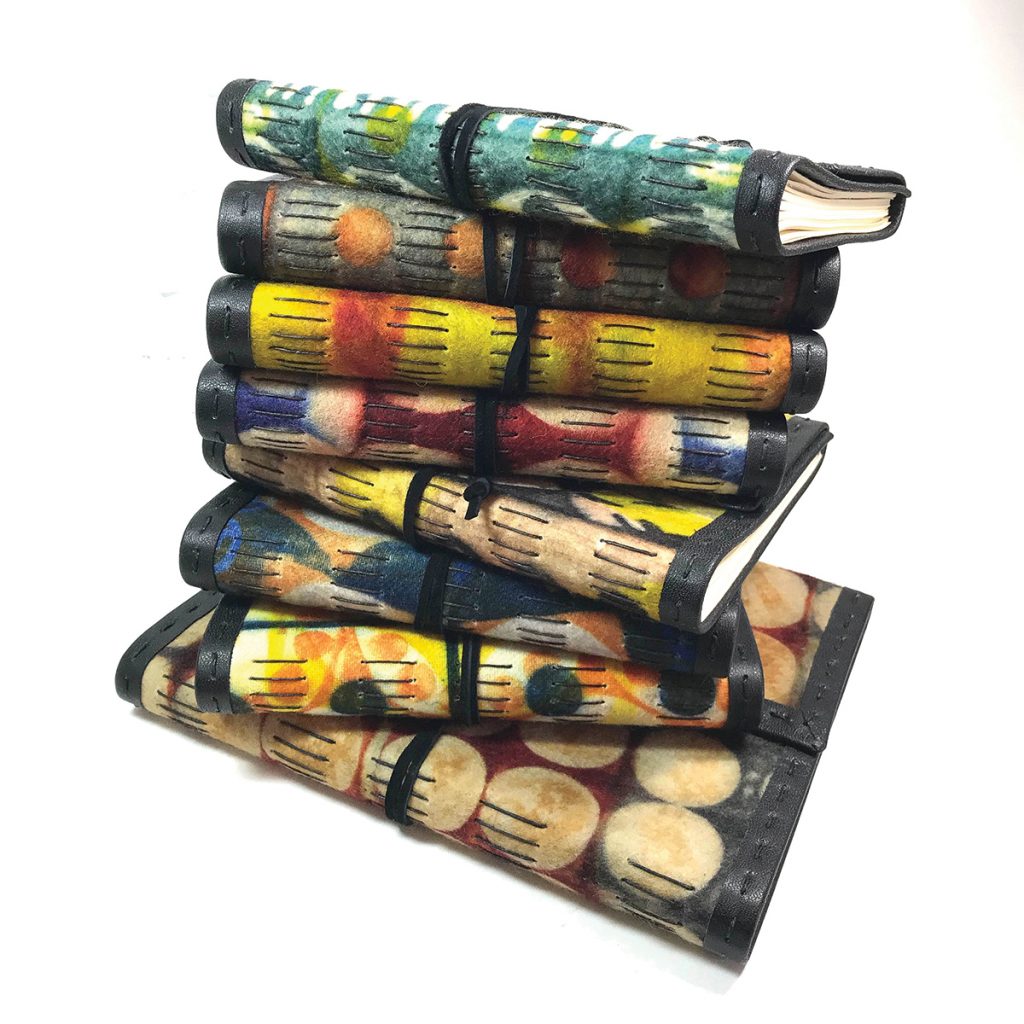

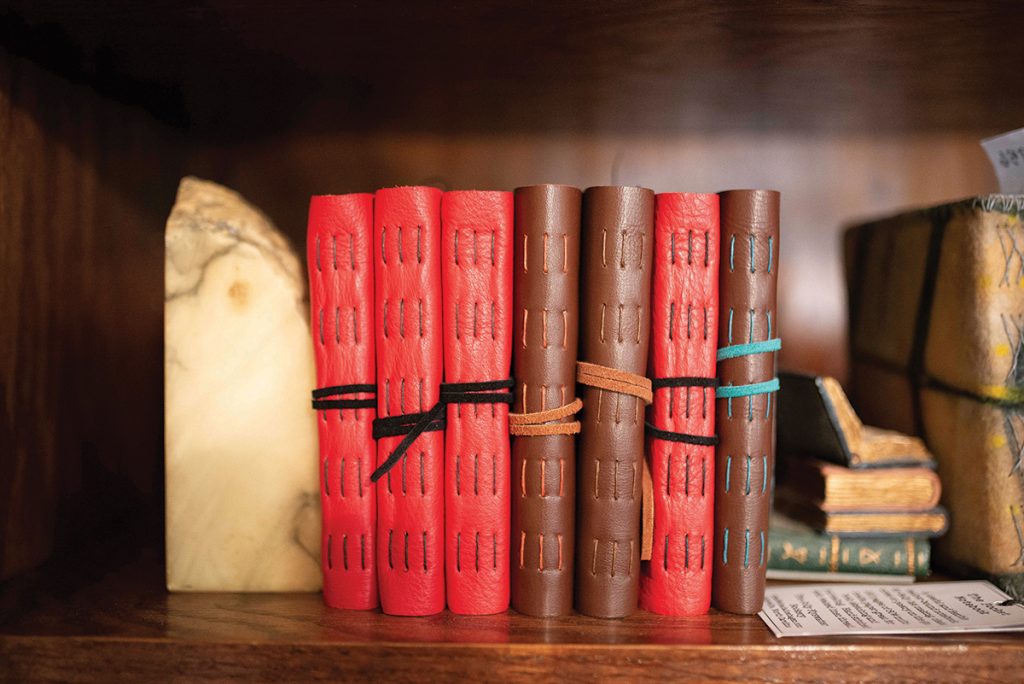

ChadAlice Hagen spends three to four days at a time in the lower level of her house, laboriously crafting handmade felt and resist-dyed wool in brilliant, original hues. Then she moves upstairs to use the felt to make bespoke keepsakes, most often book and journal covers. It’s an old-school process, and she is a master, having done it for 35 years.

Hagen herself started with blank pages in Stevens Point, Wisconsin, where she grew up, attending college in Madison before moving onto Michigan for post-graduate art studies. She soon started her professional craft career — hosting workshops and guest-teaching stints, traveling the world, and eventually teaching at Penland School of Craft near Spruce Pine.

Hagen moved to Asheville in 1997, working at Malaprop’s bookstore. She bought her house in West Asheville in 2000 and recounts tales of how the neighborhood predictably changed in 20-plus years: Once-affordable homes exploded in value, families replaced the area’s fringier characters, and empty old buildings turned to bars and cafés. Through it all, the neighborhood’s artsy character morphed but survived.

Down in her garden-level space, Haven’s expansive workshop is meticulously organized, bins of metal and plastic trinkets waiting to be used in her resist dyes. She starts with 100-percent Merino wool that comes from one mill in Australia, and hand felts it, a process that starts with water immersion and soap.

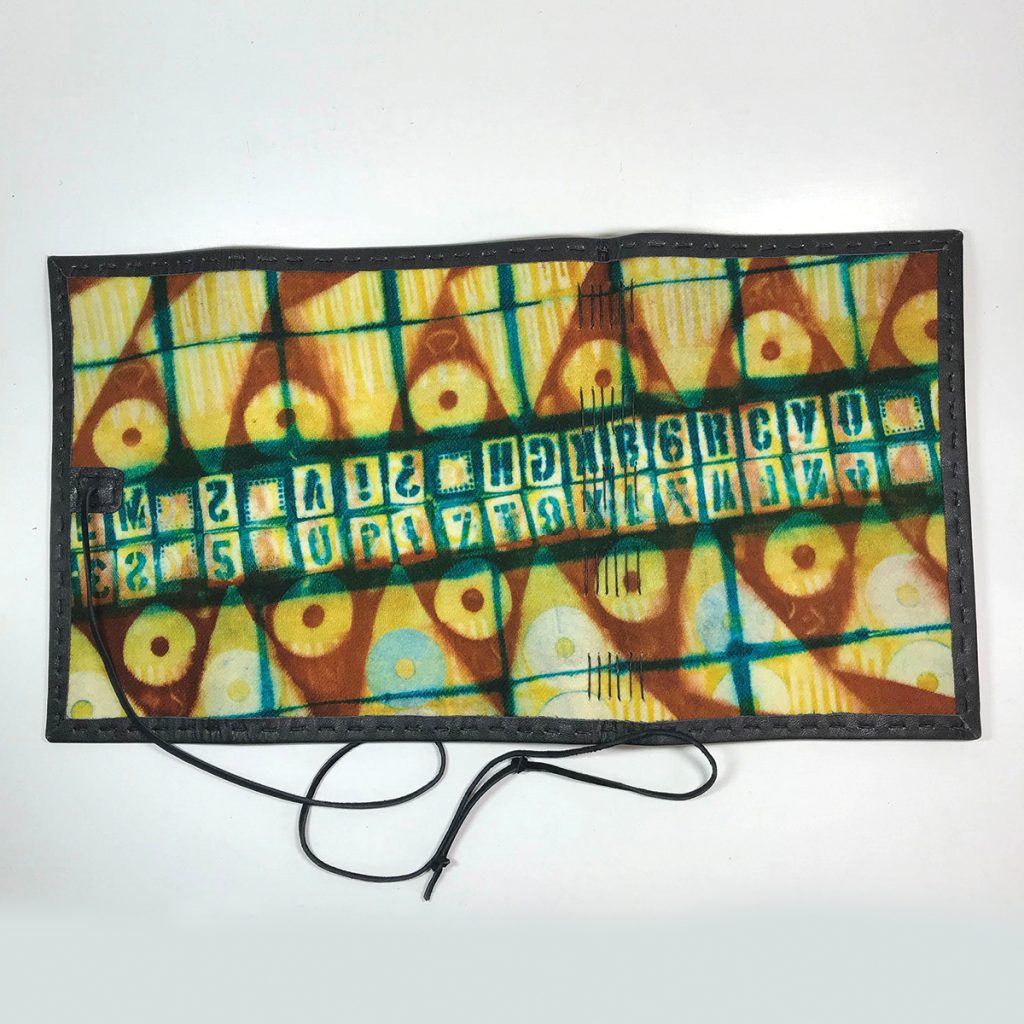

She takes the book-sized sheets of felt and clamps the trinkets — also called dye tools — inside folds of the felt. Some folds are simple, incorporating just a few tools; others have complex origami folds holding many of them. Once submerged in boiling dye, the patterns of the trinkets “resist” the dye, making an imprint of their outline in the fabric.

The pieces go through four or five dye baths before they’re complete, each bath adding more and richer colors, turning the final product into a complex tapestry with many variables. Think tie-dyed shirts, but on a smaller, more unpredictable scale.

The tools clamped to the felt can be anything small that survives getting boiled in dye, and that can be counted on to leave an interesting imprint: pieces of a fishing lure, old rotary-telephone dials, tongue depressors, laboratory items. (Craft stores also sell pre-made shapes.)

“I like aluminum, because it doesn’t bend much, and also steel washers and beauty products,” notes Hagen, who gets tools from a friend who’s worked on movie sets, and finds them herself at garage sales or in commonplace stores like Dollar Tree and Sally Beauty Supply.

It’s not all about fun scavenging, though. In the moment, if too many tools are used, they won’t clamp to the fiber folds properly.

But each tool (or combination of tools) gives each piece its own personality, and in the end, “everything seems to work one way or another,” says Hagen. “It’s sort of like being an engineer.… I never know what’s going to happen, and there are always surprises. That’s why I keep doing it.”

ChadAlice Hagen, West Asheville. Hagen is represented by Local Cloth (408 Depot St. in Asheville’s River Arts District, localcloth.wildapricot.org). She teaches workshops at her home studio; for more information, see her Instagram page: @chadalicehagen. Also visit chadalicehagen.com, her ETSY shop (chadalicehagen.ETSY.com), or contact the artist by e-mail: chad@chadalicehagen.com.