Some say the River Arts District might never have happened without Porge Buck and her late husband Lewis, who purchased the Williams Feed and Seed building at 170 Lyman Street in the ’80s, renaming it Warehouse Studios. However, if one wants to stay on her good side, calling her the founder isn’t advisable.

“Porge is the reluctant pioneer,” amends Karen Cragnolin, founder of RiverLink and the organization’s executive director for 30 years. “She and Lewis just wanted a large, light-filled space — but they did start the march to the French Broad River.”

“Pioneers?” counters Porge, without a trace of a smile. “Well, I don’t know about that. We were the first. So if that’s being pioneers, then I guess we were. Truth is, we didn’t have any sense,” she quips.

Lewis was a painter and worked in the upper floor of the building, while Porge, a printmaker, ran three printing presses, which she made available to other printmakers in a studio on the first floor. The couple rented the remaining space in the building to other artists.

Porge and Lewis met in art school in Virginia in 1950. Over the years, to afford making their art, they held several different jobs, including heading up an environmental-education program in Washington, DC. A few years later, they became innkeepers, running an old inn on the coast of Maine. It was there, in 1978, that Porge founded the Intaglio Relief Society.

Then, in the mid-’80s, they decided to move to Asheville to be closer to Porge’s mother, who lived in Tryon. They purchased an older home in the Montford neighborhood, where, Porge recalls, “we had to pour concrete over the dirt floors in the basement before we could put my two large presses in there.” The covenants governing the historic neighborhood and the restrictions against running businesses in homes became troublesome, and a sticking point eventually led them to buy the warehouse along the French Broad River.

Cragnolin says she met Porge and Lewis when she went to their Warehouse Studios in 1987, buying the building from them four years later (at this point, the Bucks had a house in Black Mountain). “[Porge] helped us a lot by holding onto the building until I could raise the money to buy it,” Cragnolin notes.

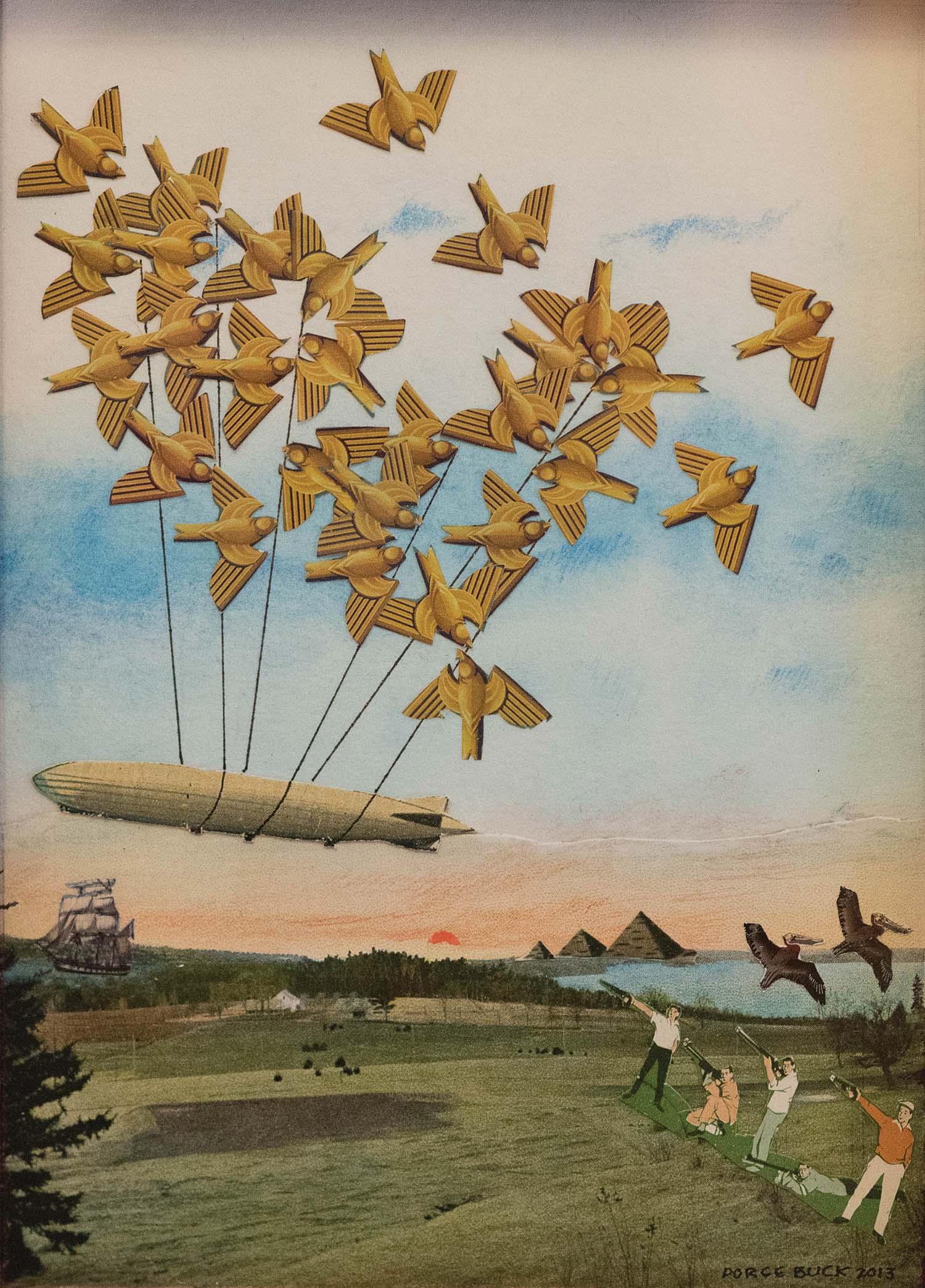

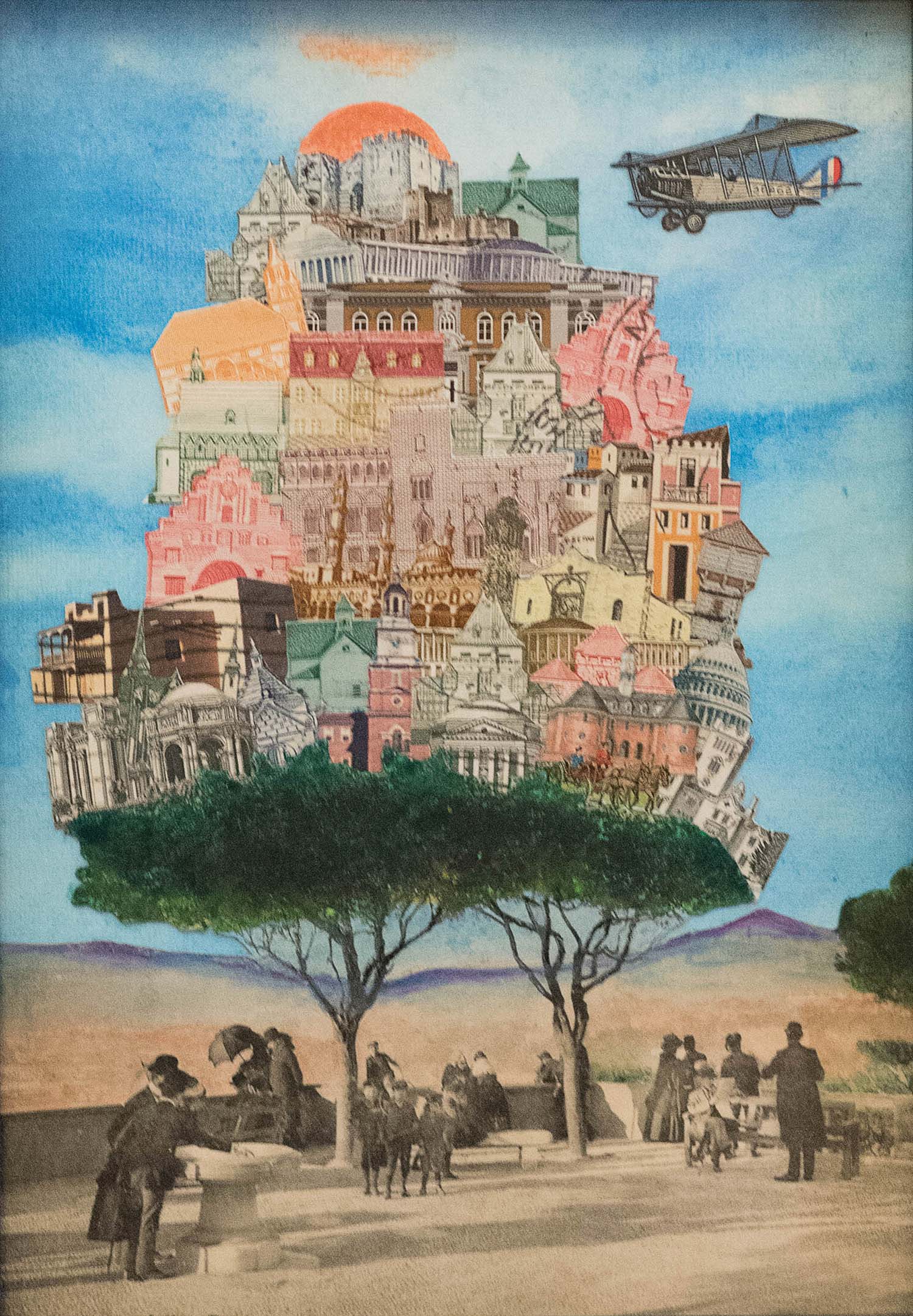

Porge and her husband each had their own studios in Black Mountain. Lewis passed away in 2012, but his paintings live on, adorning the walls of their home. Porge still makes prints (“to a point,” she says), albeit on a smaller scale than some of her earlier works. More recently, she’s begun creating small collages from historic postcards and other materials. At 87, she’s still in her studio every day, because, she says simply, “it’s what I do.”

Delightfully taciturn, she once explained why she didn’t participate in “open studio” tours: “My studio is my work space. I treasure its privacy … if someone wants to see my prints, they can make an appointment.”

Porge Buck’s friend and fellow artist, Gary Byrd, arranges her appointments. 828-215-8171.