Photo by Colby Rabon

Losing time is an important part of making art, according to William Henry Price. “Sometimes, after painting for hours, I can’t remember actually doing it — much like when you can’t remember a dream,” he says. “I couldn’t tell you what I was thinking. The gray shape turns crimson on the edges. A touch of cerulean. And somehow, four hours have gone by.”

That level of total, undirected absorption comes naturally to children — and usually gets shamed out of us, says Price, since experimentation and play are not considered productive: “It’s critical that we remove the guilt.”

To remind himself of the importance of childlike wonder, he keeps a small number “seven” sign in his studio. “When I get stuck, it reminds me to be seven years old. When you’re seven, you’re just thinking, ‘What’s the coolest thing I can make?’ You’re not concerned about how it’s going to look — no critics, no collectors. You’re in it, and you’re not trying to achieve anything.”

Using that approach, he says, “I can paint anything. ‘What would be the coolest thing here?’ is better for me than, ‘What does [the painting] need here?’”

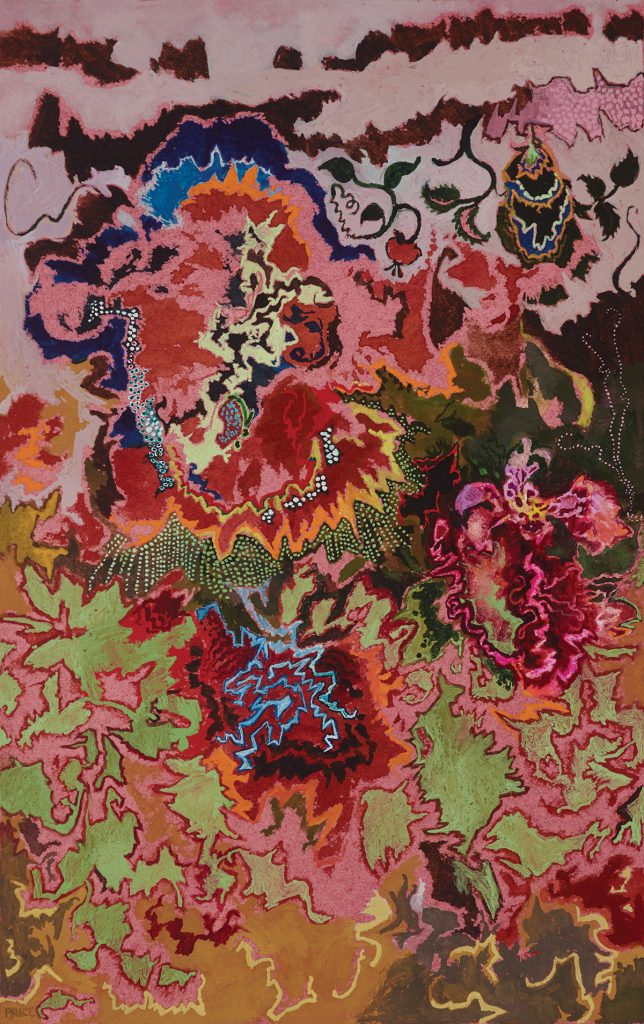

Price has embraced elements of Taoism and of Native American spiritualism, including studying with a Tuscarora medicine man in Hot Springs. He defines some of his work as “ecstatic painting,” suggesting a takeover of the subconscious, a psychedelic edge.

Even modernist masters Klee, Kandinsky, and Picasso “at some point copied the look of children’s art,” he points out. More importantly, though, “it’s the child’s unabashed engagement that we want.”Price sometimes starts his works by drawing on the canvas with his eyes closed. In this intimate mode, “I’m surprised to find I’m drawing the way sycamores ‘breathe’ in the sunlight,” he says. “Sometimes it’ll be the sound of a brook that I’m drawing, or the song of a sparrow. When you hear the sound, your hand finds the form of it.

“I never think I’m making an abstract painting. The early stages are like the way the light plays on the water, and from there it might turn into botanical growth … I want to paint the aliveness. What is it that makes a seed germinate? What mystery! Could I paint that?

“Of course you can’t. But it leads to spontaneous formal invention coming from the deep.”

He’s eager to move beyond what he calls “tight-assed scientific materialism” and toward a more sentient model of observing and absorbing nature — “a science that says, ‘As I walk in the woods, the trees know me.’ So I sit with them, notebook in hand, and we have conversations. Art is the prime way to heal our strange alienation.”

William Henry Price is represented by Momentum Gallery, 52 Broadway, downtown Asheville, open seven days a week (Monday through Saturday, 10am-6pm; Sunday, 12-5pm; momentumgallery.com). Price’s studio is at Riverview Station, 191 Lyman St. # 160, in the River Arts District; he is creating an online course and hopes to resume leading workshops after the pandemic. For more information, see williamhenryprice.com.