Photo by Colby Rabon

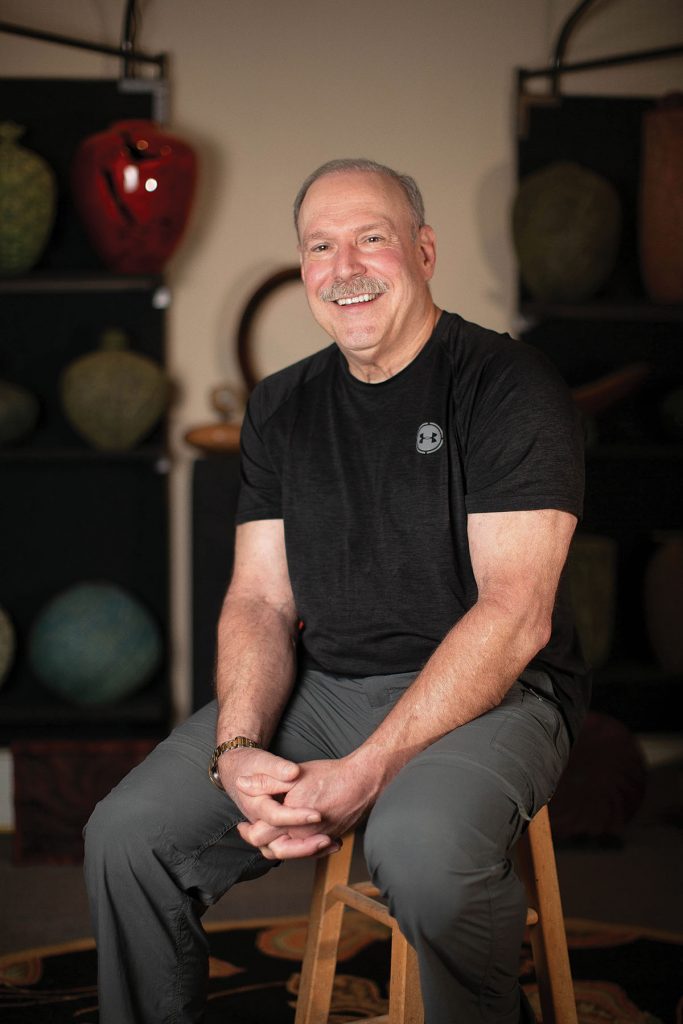

For decades, painter and television host Bob Ross reworked what he called “happy accidents” — harsh brushstrokes, paint drips, botched blending — into clouds and trees. And while that philosophy is merry enough, Black Mountain woodworker and retired Miami-Dade police sergeant Steve Miller accepts his mistakes for what they are.

Then, he sets them on fire.

“I flub up quite often,” says Miller. “But that’s why I have three fireplaces.”

Since discovering woodturning at “some art show” his wife dragged him to in 1998, Miller has been obsessed with upping the ante. But for several years, he did what most greenhorns do, settling for an aesthetic he calls “round and brown.” In essence, the woodworker masters the salad bowl, and never ventures beyond functionalism. The lathe is the first and last stop.

In 2016, worn ragged by making kitchen accessories, Miller attended a two-week class at the Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts in Gatlinburg, Tenn. He studied under Jacques Vesery, a sculptor renowned for his immensely intricate carvings. Vesery introduced Miller to the joy of form —the beauty of color and texture. Though Miller struggled for the first four days, what he calls the “limitlessness of carving” soon clicked. And by the course’s end, Vesery had invited Miller to serve as his assistant for a woodworking class in Maine.

Photo by Colby Rabon

“Without Jacques, I would still be rounding and browning,” Miller jokes.

His “Finial Forms” series — a collection of sculptural vessels topped with accents — echoes Vesery’s proclivity for detail. Inspired by the coral reefs of Florida, one piece flaunts hundreds, if not thousands, of hand-drilled crevices to mimic a reef’s porous exterior.

The process demands patience. After sourcing his materials from local woods — ice-storm-felled trees, for instance — and trash piles, Miller turns the wood on his lathe. “Everything starts as a log,” he explains.

Photo by Colby Rabon

The log is then rough turned to the approximate shape, and allowed to dry and warp, before Miller can turn it again to achieve the correct thickness for carving. Even with high-speed dental drills, carving can take months.

“I could make a lot more money flipping burgers,” says Miller. He reveals the process behind his Albizia Rootball Hollow Vessel, a blood-red vase in his “Naturals” collection: “After digging up the rootball with a backhoe, a guy had to drop the entire rootball, encased in mud and rocks from being underground, in my driveway with a crane. It weighed 500 pounds. Then I pressure washed it for ten hours to remove all the mud and rocks.”

Photo by Colby Rabon

Again, Miller’s way is not for those artists who seek immediate gratification. He works on about 100 different pieces at once, jumping from process to process to avoid fatigue. His newer sculptures, including a charming series of “hand helds” designed for smaller living spaces, are vibrant; each piece is dry brushed with 20 layers of acrylic paint for depth. This might be the trickiest step for Miller.

Photo by Colby Rabon

“I’m colorblind,” he admits. “I have to ask my wife and take her word for it. To me, everything is just brown.”

There’s that word again: brown. Lest he slip back into the mind-numbing depths of “round and brown,” Miller must make mistakes. And when the accidents happen, because they will, acceptance is the first step, and fire is the last.

Steve Miller, Black Mountain. Miller is represented by Bella Gallery (112-A Cherry St, Black Mountain, bellagallerync.com). For more information about the artist, see naturesturnwoodturnings.com.