David Ellsworth, a turner of delicate, thin-walled wood sculptures, is always aware that his tools might puncture the surface of his works and ruin everything.

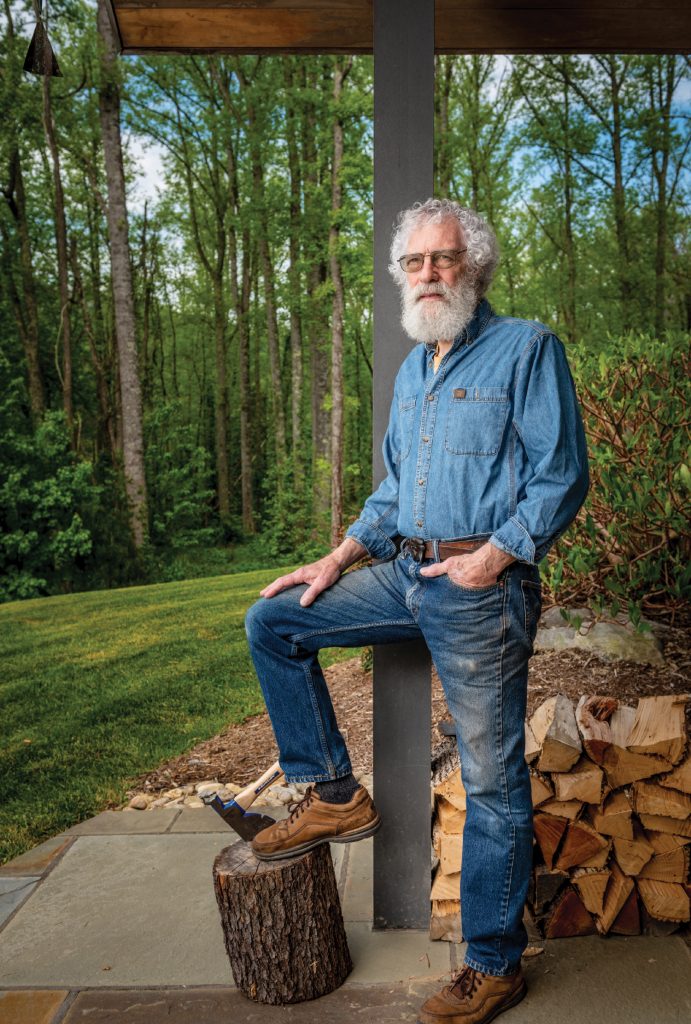

Portrait by Paul Stebner

That’s the real-life danger. Then there’s the metaphorical threat. “Even the thought of making art, much less the act itself, is mired in risk,” he offers. “[But] risk is part of its value.”

And yet his legacy seems safe: Ellsworth has become a well-respected teacher of the turning techniques and tools he’s developed. “I know how it feels to do work through a process of feel rather than sight. That intimacy needs to be reflected in the final form.”

To convey this to his students, “I talk to them about reaching into a hollow

form with a sharpened piece of steel and learning to ‘shake hands’ with the wood,” he says. “At some point, a thin wall will radiate a tone that [the student] can follow throughout the form, whereas a thick wall must be mechanically measured.”

Ellsworth was 14 when he was introduced to the lathe in an eighth-grade wood-shop class. “I made a platter out of 24 pieces of walnut glued together, for my mother,” he recalls. “I discovered lathe work was a centering process, and it was liberating.” He continued turning wood until he graduated.

That was put on hold, however, when he enlisted in the U.S. Army. Afterward, at the University of Colorado, he earned a BFA and an MFA with an emphasis on sculpture, training in ceramics, cast bronze, aluminum, and carved stone. “In grad school, I worked entirely in casting polyester resin. Horrible material, but beautiful results.”

Wood, however, was never far away, thanks to Ellsworth’s professional discipline. “I made furniture on the side throughout school and ran the university woodshop for extra cash during my graduate work.” In 1974, Ellsworth was asked to start a woodworking program at the Anderson Ranch Arts Center in Snowmass Village, Colorado. “I knew woodworking machinery and most construction processes. But suddenly, at age 30, I was a teacher.”

He also learned something: If he really wanted to make a living in the arts, he had to create functional items. “I developed a set of salt-and-pepper and sugar shakers … about 5,000 pieces, $18 for a set of three.”

In the evenings, though, he was inclined to experiment, covering the shakers and making hollow forms. “As the openings began to shrink, I realized I needed to bend my tools to reach the interior areas. I began to push the wall thicknesses thinner and thinner, for no reason other than the obvious challenge.

“The end result was that I had found my medium, and the passion was back.”

Still, it took more than two years of trial and error until he achieved an elite delicacy — forms eight inches in diameter, three inches high, with only a 1/16-inch wall of thickness throughout, “hollowed out through a one-inch diameter hole,” he describes.

Ellsworth’s “Homage” series honors the landscape and architecture of the American Southwest. Another series, “Spirit Form,” was inspired by a Hopi-Tewa woman: “She made tiny pots with beautiful painted surfaces done with yucca-fiber brushes.”

Despite decades of experience, Ellsworth says he can still be surprised. “It’s a consistent part of the making process. Without surprises, objects become predictable.”

David Ellsworth, Weaverville. The artist is a founding member of the American Association of Woodturners and served as the organization’s president from 1986–1991. Ellsworth’s work can be seen at Momentum Gallery (52 Broadway St., Asheville, momentumgallery.com), with a show opening Thursday, June 27 (reception 5-8pm), and running through the end of August. For more information, including studio appointments, see ellsworthstudios.com.